Project 360

Table of Contents

_

situated / having a site, situation or location

worldbuilding / the creation of an imaginary world, with its governance, economics, social relations and cultural influences

Building without money, power or land

A tall order to be sure, but a challenge that we approach through the portal of our research question, so to speak - "In the future, how will we solve problems to which architects are currently our best answer?"

It gives us an opportunity to dismantle professional practice, not so much into its constituent parts, but rather into the various the dimensions of its outcomes, that professional practices may have delivered. We can then reverse engineer these into alternative devices for development.

It would be unreasonable to expect that any candidates for the title of 'solution' would resemble existing professional models. As we have previously observed, "practice is not a single, ‘inevitable’ sequence of actions but a constantly evolving collection of codes, simplified for social, legal and commercial purposes under the brand of 'Architecture'".

The process of reverse engineering involves interrogating these codes, developing or elevating those with values that we can confidently promote, and reassembling them into spatial practices that answer challenging questions.

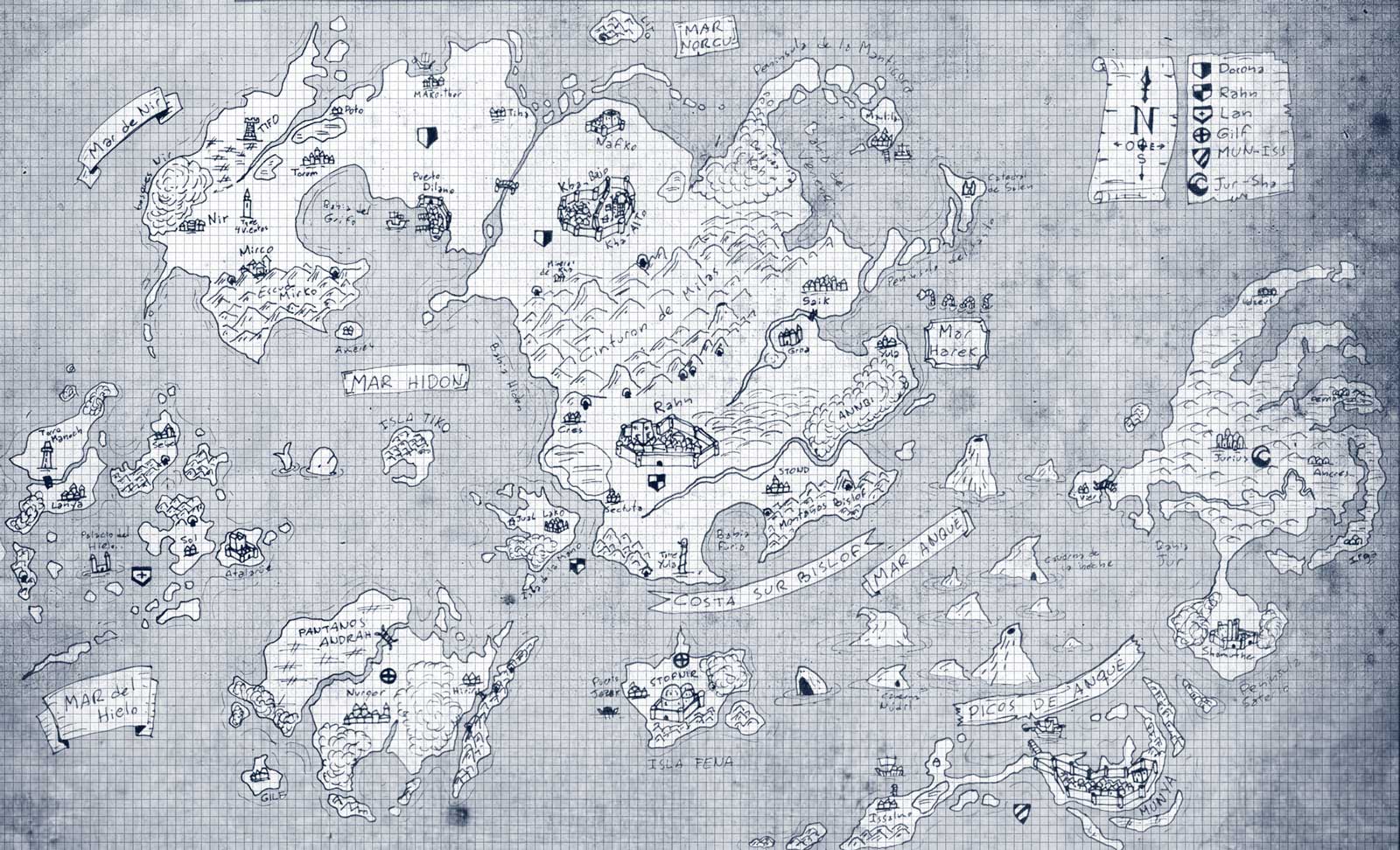

One device that we aim to employ, towards this end, is worldbuilding.

Critical worldbuilding

Writer Trent Hergenrader sets out four major categories (governance, economics, social relations and cultural influences) and 14 sub-categories as primers to establish the parameters of a fictional world.

Given that these structural categories need to be pursued with enough sincerity to stimulate suspension of disbelief, we have the opportunity, at the same time, to examine the potential for alternative real worlds, with real details.

These are the contingencies that architects so famously like to side-step. So-called contingencies actually provide the foundation for stimulating genuine, alternative possibilities.

When worldbuilding is situated, a broad spectrum of concerns is dealt with, in the real world, by default.

Collaborative worldbuilding

While the worldbuilding of an author such as J.R.R. Tolkien is a solitary affair, the collaborative variety involves interactive, group creativity. A game of Dungeons and Dragons is a perfect example.

Hergenrader's model for building worlds is as good a place as any to start this journey.

It breaks down as follows:

Governance

- Government presence

- Rule of law

- Social Services

Economics

- Economic strength

- Wealth distribution

- Agriculture & trade

Cultural influences

- Race relations

- Class relations

- Gender relations

- Sexual orientation relations

Social relations

- Military influence

- Religious influence

- Technology influence

- Arts & culture influence

All of these building blocks are assembled towards a public presentation of a new world, to set the stage or storytelling or gameplay. Let's call this public presentation ‘front-of-house’.

Front-of-house / back-of-house

In the design industries, we are very familiar with front-of-house promotion – “look at my beautiful building!”. In fact, architecture is overweight this kind of promotion underweight back-of-house analysis – what really is involved in starting a practice? How do you run that practice? How do you grow it?

A London architectural duo running a “research-based practice” recently gave a talk which included an interesting project in Australia, where they flew out to work on it for months, and a bold, self-funded development in the UK. If we put design questions aside for the moment, we are left with quite fundamental ones. While they were away for months on end, how did they pay the rent or mortgage? How did they eat? Was this one long-distance project enough to sustain them? Clearly, there was a very significant part of the story that was not being told.

Or a celebrated collective, building award-winning projects straight out of university. How did they pull that off? If this is broadly achievable for graduating students at large, then surely gold is to be found in their story, regardless of the creative awards. We assume they weren’t hungry or living on the street as they started up. Have they been able to sustain that early idealism, or must practices like this eventually revert to more traditional models? Can their youthful idealism survive the social and financial demands of a house purchase, a pregnancy, or a marriage – in short, real life?

Architecture also depends on these contingencies, it's just that they are of the back-of-house variety. They also should not be ignored.

Architecture is the most elite profession in the UK, with 73% of its members coming from privileged backgrounds. Perhaps this goes some way to explaining so many of the practice stories that do not get fully fleshed out.

Every company is a media company

“Today, if you look at other industr[ies], [every] single company is a media company, and connection and engagement and interaction and the way in which we approach digital or social, make the huge difference that we experience today”

Insight from the head of Gucci, Marco Bizzarri.

If we embrace the assertion that space is a medium of communication, Bizzarri’s statement can be taken as a call to arms – not just for spatial enterprises to engage with media, but to re-conceptualise what that relationship might look like.

This pursuit takes us back to the first principles of back-of-house organisational structure.

A production model

Design professionals typically engage with the outside world via a consultancy/agency, work-for-hire model – a client engages you or your team for your specialist skills, to advise on a project on their behalf, usually with the actual work, be it building or physical printing, carried out by third parties.

There is, however, the potential for a different approach.

First, a brief history of architectural practice.

The role of architect has, particularly over the last hundred and fifty years or so, evolved as a class–based construction – employing methods of division to position itself with regard to others, such as ’higher’ owners (clients), and to elevate itself above others, particularly ‘lower’ builders and other construction specialists. The result is a rigid and hierarchical division of labour which, coupled with the needs of local regulatory environments, has given us various forms of protection (title and/or function) and, it must be said, an element of insularity in the profession. Nevertheless, over this same period, the role of the architect been fluid and in a constant state of play.

Collaborative worldbuilding is possible with a work-for-hire model, but not optimised for it. Back-of-house, it is much better suited to a production model.

Why not borrow (steal) business ideas from production houses around the world – in theatre, film, game design and more?

Structurally, production models are a form of vertical integration - owning and/or having direct control over a full creative stack from ideation to execution and use.

The division of labour that this opens up is not so much hierarchical as it is departmental - self-contained but collaborative teams that specialise in a specific aspect of the production.

A back-of-house team might start from a template of five departments, alphabetically …

- Communication

- Interactive

- Maker

- Spatial

- Story

Rather than awarding uppercase-letter titles, a collaborator might simply be tagged: #comm, #intv, #mkr, #sptl or #stry

This de-professionalises statutory and class-based barriers to entry, and opens up the collaborative audience to the wider public.

… so if we go back to our traditional ‘hero’ architect, their ‘heroic’ status is ‘demoted’ to spatial, and say a builder’s is elevated to maker.

This sets the stage for meaningful collaboration.

Achieving meaningful collaboration

Collaboration is another one of those words in heavy use in marketing and the media. In some contexts, it carries a lot of weight, and in others, it is simply an appliqué label.

For collaboration to be meaningful, departments should be in a position to contribute comparable levels of input. This has creative as well as legal implications.

Creative

Our North Star is a perfectly egalitarian division of input. However, the realities of site-specific project requirements, the quantity, and availability of prospective team members and the nature of the sequence of the initiation of the idea, will mean that, in practice, some departments will have more weight than others.

But the ideal is equality.

Legal

The prospects for achieving meaningful collaboration are won and lost here. It may not be sexy, but interdepartmental creative equality is only possible when there is similar egalitarianism in ownership and control.

There is no need to reinvent the wheel. There are many models which allow organisations to share ownership (e.g. employee benefit trusts - Make Architects, Zaha Hadid Architects and others) or control (e.g. holacracy - Impact Hub Company, DTP and others)

However, meaningful collaboration requires both, and for that, we have other possible business and collaborative systems or protocols:

- Cooperatives

- Decentralised Autonomous Organisations or DAO’s

- … and one particularly interesting, emerging possibility, Holochain

Challenges

It is critical that projects remain grounded, literally.

This means going beyond just software or gadgets, to make a tangible impact in the real world with real people. Projects that are site specific are best placed to achieve this goal.

However, location-based interventions typically present three key hurdles:

Technical

Stakeholders have to navigate a regulatory maze to move building projects forward – requiring knowledge, qualifications and financial barriers to entry, such as professional indemnity insurance, that non-industry city dwellers do not have. Typically, surmounting this hurdle requires a consultant team.

Inclusion

The elitism of the architectural profession is most pronounced in urban areas, where ethnic minorities are particularly underrepresented. For example, in London, with 46% of its population from Black and Minority Ethnic groups, only 11% of architects are from the same groups, of which only 1% are black.

Land ownership

City dwellers typically do not own the land that they use on a day-to-day basis. Since 2016, the number of renters has surpassed the number of homeowners in London. Unsurprisingly, most commercial and public properties and open spaces are not owned by the people that use them. This presents a further restriction on the ability to transform these spaces.

If we do indeed have a land crisis in a developed country such as the UK, urban interventions will demand non-traditional answers to the land question.

Opportunities

Each of the three challenges above has a head-on potential solution, which will be explored.

But the low-hanging fruit solution that deals with all three at once, is to incentivise transformative behaviour. This is one, foundational way to give communities agency to build a new world to live and work in.

This flavour of creative practice is best placed to touch the ground temporarily, lightly or not at all, while remaining site specific … and potentially open to all!