Assembling the Architect

Over the years, the role of architect has been fluid and in a constant state of play.

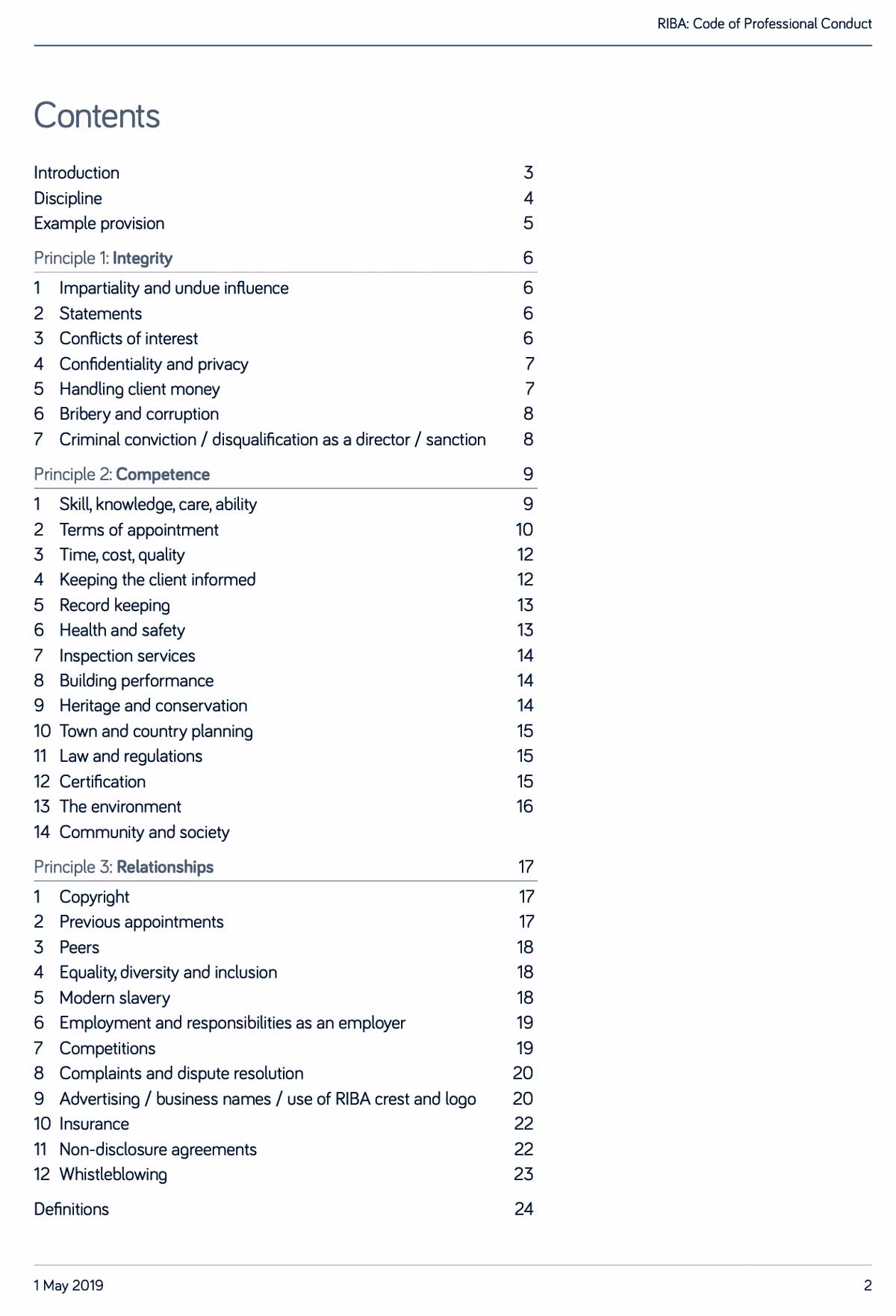

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, Re-imagining architectural practice

A class sandwich

The role of Architect has, over the years, been fluid and in a constant state of play. Lurking beneath this fluidity, however, is a preoccupation with class.

The architecture profession has employed methods of division to position itself with respect to others, such as ’higher’ owners (clients), and to elevate itself above others, particularly ‘lower’ builders and other construction specialists. The outcome of the means and acts of this stratification has been a profession erecting a protective (protectionist) ring around itself.

The obsession with class, manifested through gentlemanly and derivative codes of conduct, has been an active subject of debate for over a century. In that time, the societies in which this stratification has been employed (the West in particular) have experienced hugely transformative economic, technological and social–cultural upheaval. The hidebound practices of the profession have succeeded somewhat in their protectionism, but this has come at the cost of a lack of evolution, bordering on stagnation, as the rest of society gallops by.

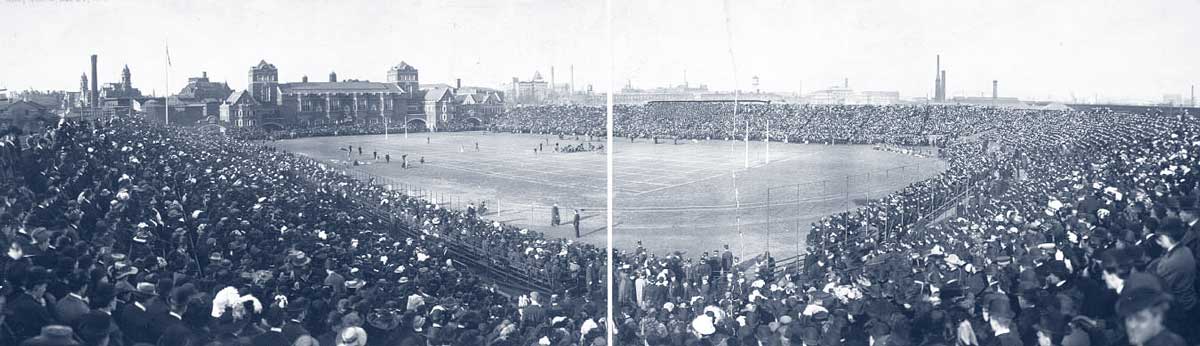

And so, within this frame, the story of how the profession of architecture was assembled around the turn of the twentieth century is one of a rigid class system, providing the backbone to the status of the architectural profession, versus a fluid and evolving business, cultural and technological environment both engendered and exploited by owners above and builders below. Architects, in the middle of this class sandwich, have therefore been forced to adapt and evolve.

"We are in a very different reality today, one in which capital’s endless drive for profit has degraded the architectural craft and produced a more exploitative workplace for architectural workers of all kinds." @arch_workers_u https://t.co/rEVB0Lo2wq

— Department for Professional Employees (@DPEaflcio) July 18, 2023

The role of Architect has, over the years, been fluid and in a constant state of play. Lurking beneath this fluidity, however, is a preoccupation with class.

The cast of actors

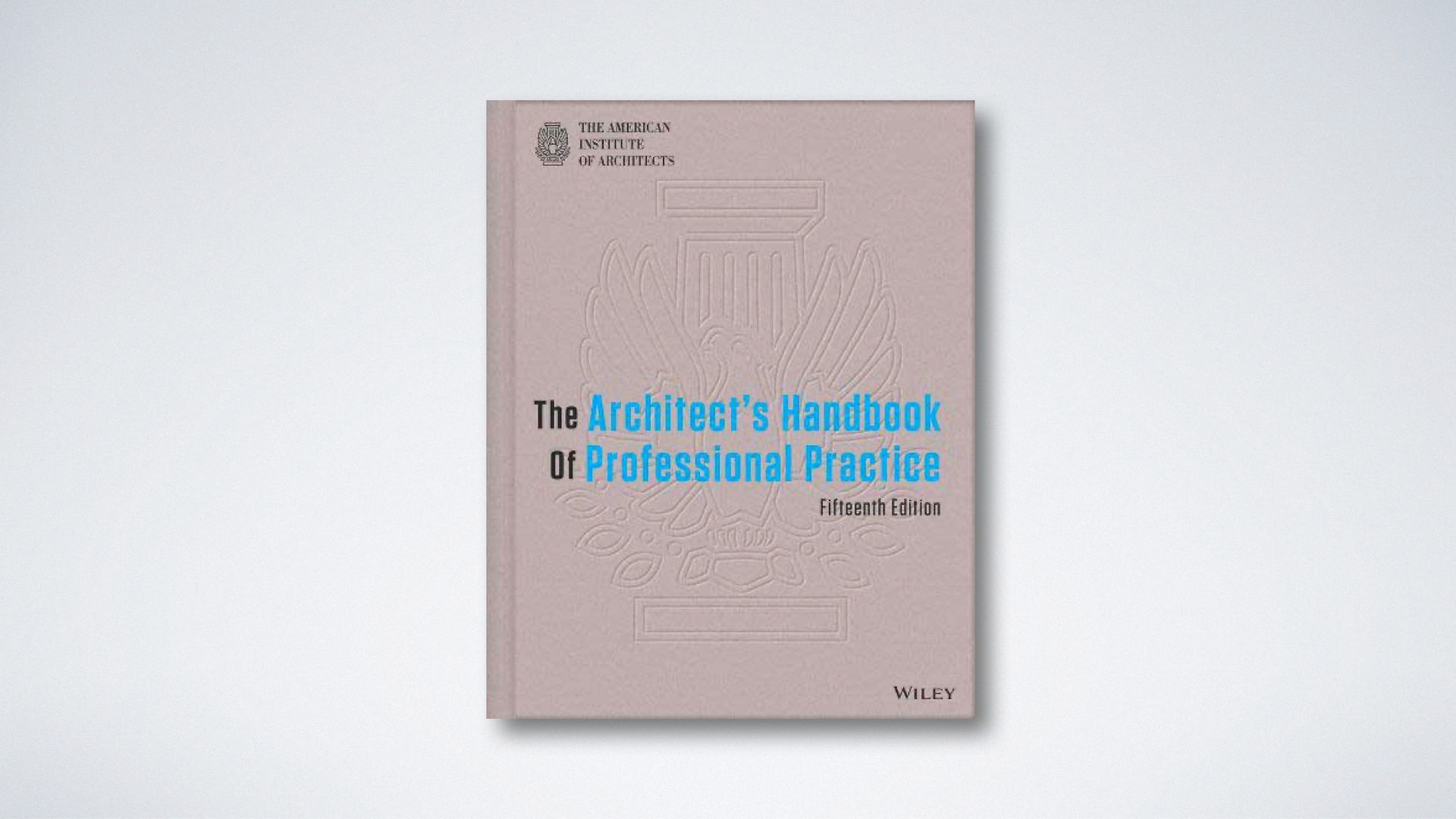

Johnston’s barometer, giving readings on the state of affairs over time, is The Handbook of Architectural Practice, first published in 1920 and evolving with the complexity of the industry.

Assembling the Architect primarily concerns itself with the shifting relationship over the years between architect, owner, and builder – its main cast of actors. However, it also engages with other relationships, such as those with engineers and technical specialists such as landscape and interior designers.

Originally, the work of architect Frank Miles Day, the Handbook began as an office manual and evolved into a business administration guide, ultimately laying the groundwork towards recognition of architecture’s professional status in the United States.

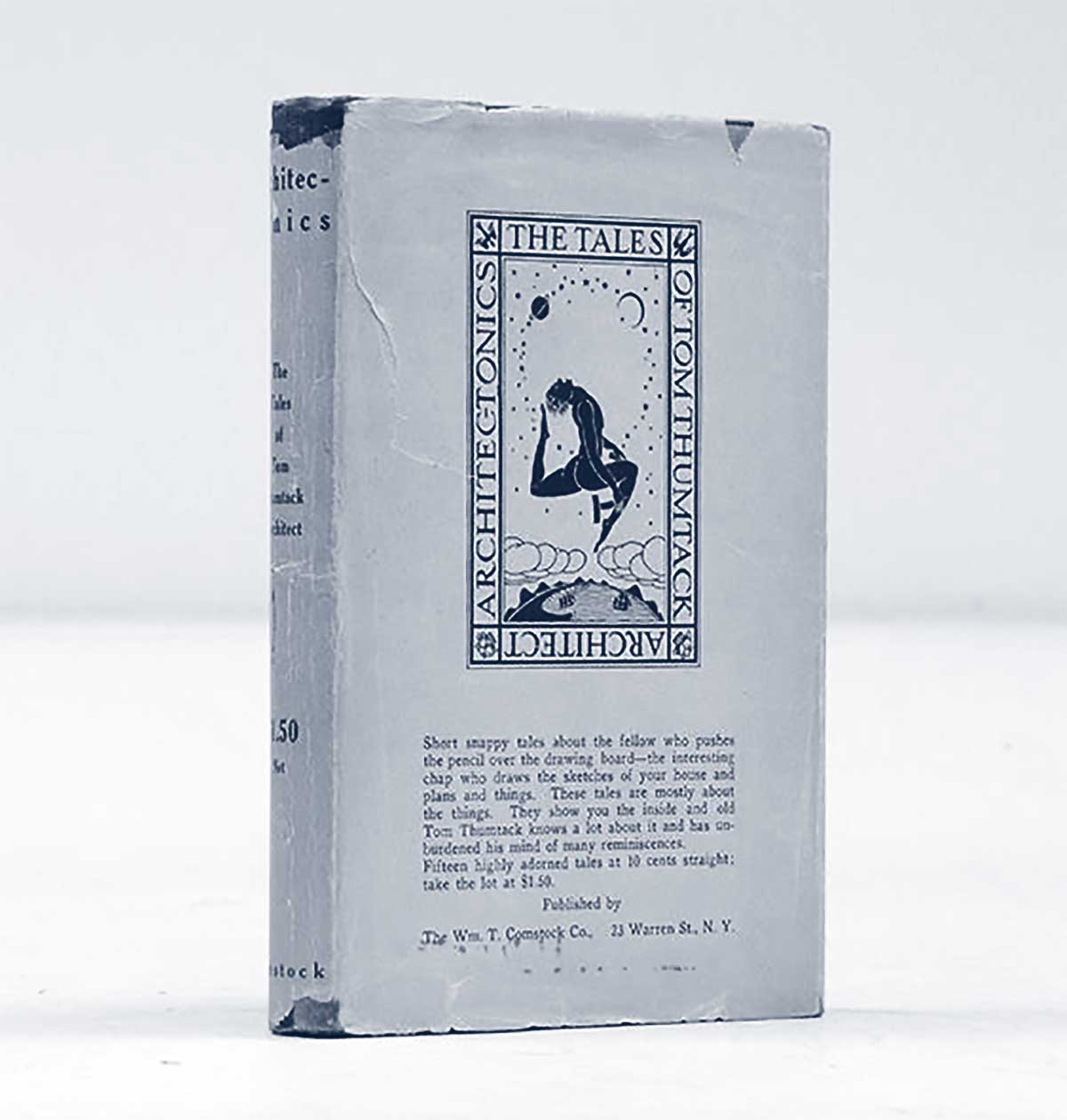

This barometer of practice is monitored alongside its contemporary, the fictional, satirical Tom Thumtack’s tales, by Rockwell Kent, a commentary on architectural practice of the time.

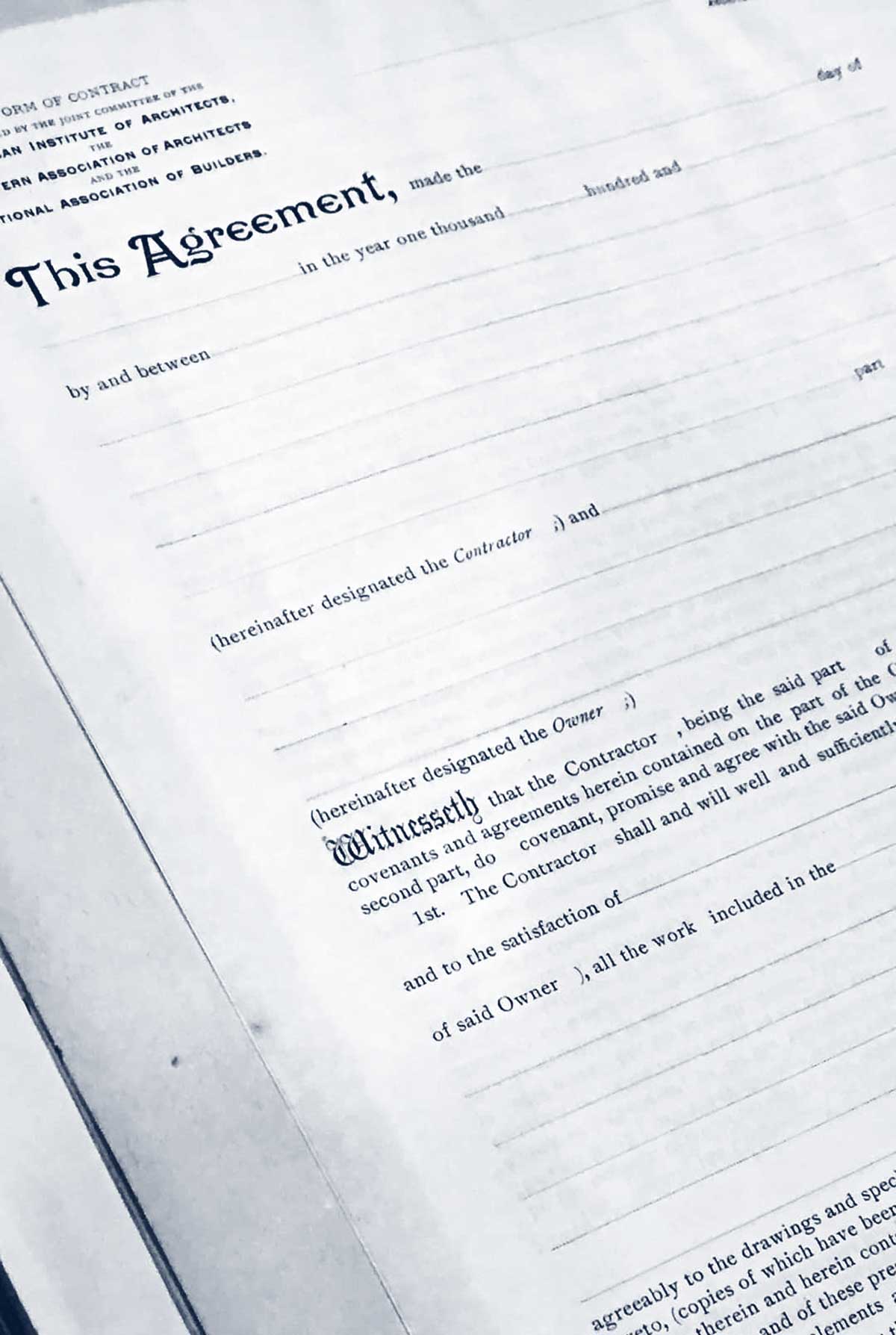

Lastly, Johnston assesses these two publications against the backdrop of a further, the development of the Uniform Contract of 1888, for use between owner and contractor.

Division of labour

The handbook was a response in part to the perceived practical deficiencies among architects in business acumen, and a similarly perceived over-emphasis on the artistic side of the profession. Indeed, the author’s reading of the early handbook reveals the assertion that “it was only through the primacy of an efficient organisation, constantly evolving in harmony with the new methods of business management that the designer will be free to exert his creative and artistic talents.” In addition, it reflected the consequences of the division of labour within the industry, which typically left the architect with a more narrow agent/consultative role.

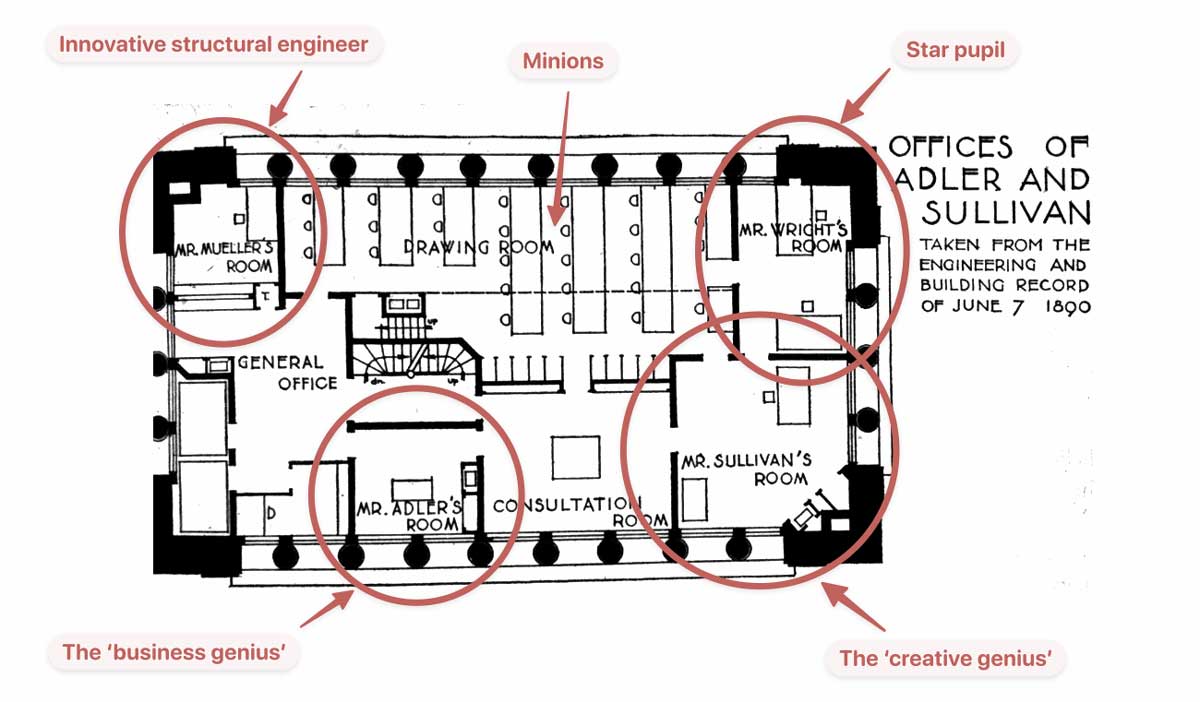

In the fictional tale of Tom Thumtack, we encounter the notion of the spatial organisation and spirit of the architect’s office as a manifestation of his business structure and values. This remains with us today, though more intertwined with the romantic notion of the artist’s studio than the technical principles of a business plan. Nevertheless, once populated by staff, the personal and informational flows through the office can be codified in The Handbook – simultaneously a trigger for activity and a record of the history of those activities – the software of the firm.

It is fascinating to read the author’s description of the entry sequence for clients from reception through to meeting with senior staff – a route with visual cues via organisation and portfolio displays, representative of what the firm stands for. It is a veritable promenade architecturale, framed as an exhibition – a narrative environment so-to-speak that was “an experiential advertisement for a profession that otherwise frowned on advertising in print”.

The office layout itself was an expression of a further division of labour – representative of the hierarchy within the firm. Unsurprisingly, the grunt work, back office staff are hidden away, lest they burst the illusory bubble.

Likewise, the preoccupation well over a century ago with the promotion of architecture as a fine art – gallery mounted and all. And, as today, the irony that the primary audience remains fellow architects rather than the public at large, who seem to show little interest compared to the blockbuster plastic fine arts shows. It is perhaps unsurprising then that architecture’s contemporary image-ready leaning towards the sculptural and dramatic, devoid of social or practical contingencies, sells better with the public from an exhibition/coffee table book standpoint.

One’s standing

Barnett Johnston’s vocabulary throughout hints at the social context of architecture and the firm at the turn of the 20th century, similar to today – a setting which drives decision-making and possibilities, where the opportunities for practice via wealthy clientele rest on a foundation of social and class standing. This is not explicitly stated, but implied, in the descriptions of the evolution of codes of practice, and particularly the detailed accounts of the character’s lives, some of which lean towards society, memoir–style writing.

This is a minor criticism, but perhaps it is simply emblematic of the realities that we still deal with as professionals serving the elite and powerful commissioners of our work. Regarding architectural registration, Johnston does make the connection between the idea of reputation that comes with registration, and class – highlighting that the differentiation between professional architects and design-builders is as much a question of practice as it is of standing in society.

Again, the social stratification, though representative of the time, still echoes today – with women in prescribed (non-technical) roles, and not a minority (black, Latino, Native American or Asian) in sight.

Barnett Johnston reminds us that the post-First World War era, when the Handbook was written, was one of huge technological and economic transformation. However, major social transformation was still to come.

Catch 22

In traditional procurement, the owner-architect-builder relationship has a built-in flaw – namely the conflict between the architect’s role as independent arbitrator (between owner and builder), and that of client’s agent. It immediately begs the question of how an architect can act independently for both parties (say as Contract Administrator of a building contract) when in fact he was hired by an acting for one of the parties – the owner. The architect depends on tangible qualities to justify this dichotomy – his statutory registration and/or membership of a body of his peers, such as the RIBA or AIA, and the codes of conduct that come along with them. He also leans on intangible qualities – his ‘professionalism’ and an implication of honour, gentlemanliness, and the pedigree of these qualities amongst his brotherhood – class-based qualifications of integrity.

Then and now, however, the builder and the owner have recourse to external legal procedures if the architect’s agent/independent arbitrator’s dichotomy is not resolved – a backup class leveller of sorts.

A social practice

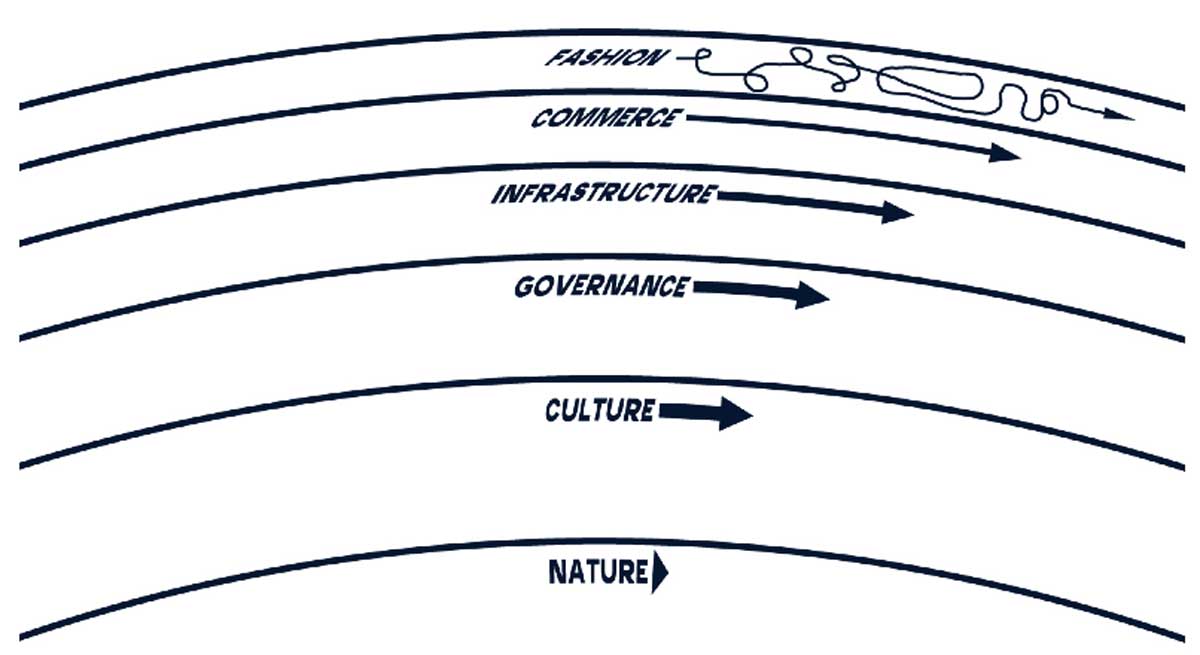

In the latter stages of the book, Johnston switches on his inner sociologist, framing the practice of architecture in its historical context through the act of “constructing design as a social practice situated both culturally and structurally in the American context “, with the architect’s tools framed as “bundle[s] of social relations” – be they contracts, drawings, or the offices and staff themselves.

In this framing, the profession of architecture is an emergent, after the efforts of individuals and groups within a particular socio–cultural context and anchored by the weight of history of the idea of architecture.

Practice is therefore not a single, ‘inevitable’ sequence of actions but a constantly evolving collection of codes, simplified for social, legal and commercial purposes under the brand of ’Architecture’. The standardisation professed by The Handbook of Architectural Practice was less an account of agreed principles and more, over the years, a self-fulfilling prophecy of the progression in an increasingly interconnected nation.

Practice is therefore not a single, ‘inevitable’ sequence of actions but a constantly evolving collection of codes, simplified for social, legal and commercial purposes under the brand of ’Architecture’.

The old and the new

Johnston shows that, with the benefit of historical context, alternative modes of practice seemingly stimulated by new technology such as BIM or management principles such as IPD are more cyclical than they are disruptive, returning to some of the ‘pre-professional’ arrangements of the 19th century - “… resuscitating the hybrid disciplinary agencies of the past”.

Given that we are on the cusp of further significant technological and social upheaval, the profession is poised similarly as it was then.

Before, a budding profession called Architecture.

Now, with different codes and bundles of social relations, a new profession will emerge that has not yet been named.

Author: George Barnett Johnston

Year of Publication: 2020

Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

The future of architecture is not what you think

Follow to find out what it might look like.