Re-imagining architectural practice

How, in the future, will we solve problems to which architects are currently our best answer?

Table of Contents

A civilisational biopsy

This is the definition of compound, concurrent heat extremes! What you're looking at is the pressure pattern & wind flow at the 500mb level (5600 m, 18K ft). This is why Death Valley hit 129, the Med may hit 118, Iran heat index 152F and China hit an all-time heat record of 126. pic.twitter.com/qlXnoaAMmq

— Jeff Berardelli (@WeatherProf) July 17, 2023

This is not a post about climate. It just so happens that this past week has brought enough attention to climate change to shift the media conversation into the realm of the dramatic. However, despite the intensity of the drama, it hasn’t stopped the deniers or the side-steppers. Not even the drama of this week!

Scary in the movies.

— Hugo Tagholm (@HugoSAS) July 14, 2023

Even more scary in reality.

As the climate crisis builds, so does climate change denial.

🌎🔥⛽️❌

pic.twitter.com/8cBkPrBg0C

Incredibly, this was not the only recent civilisational crisis, at least in the UK.

Rents outside London, where many priced-out Londoners have fled, have risen by a third in only four years. You’ll spend a long time looking for workers whose salaries have risen comparably, unless, of course, you found the King. The rent situation is only one symptom of the UK’s housing malaise, driven by post-Thatcher, post-great-financial-crisis bubble economics of hyper-liberalisation, ultra-low interests rates and an avalanche of international money.

In the 90s we needed Ali G.

— Aaron Bastani (@AaronBastani) July 4, 2023

In the 2020s people just being candidly honest about their business model, and how fucked up it is, is more surreal than any satire. pic.twitter.com/5U8pjgyqu8

Meanwhile, the government, itself in crisis, has announced a crackdown on “rip-off university degrees” - linguistic cover for an actual crackdown on studies that are too far off the UK’s financialised train line. The prospects of UK degree programmes are now inversely proportional to the level of critical thinking that they stimulate. Who knows, some architecture programmes may even get the cull.

The prime minister, speaking not only for his party, but for all those who share his values, said the quiet part out loud - that universities are “full of, you know, people who don’t vote for us anyway”. To hell with your aspirations.

Over the pond, the continental US property industry has been literally bracketed by the withdrawal of major insurance companies from California (west coast) and Florida (east coast), presumably because of ‘unbearable’ losses from fire and hurricanes respectively.

What we are seeing here is a snapshot, a biopsy of sorts, of the current state of Western civilisation; or perhaps the edges of the anticipated polycrisis.

Imagine a World War. What are its characteristics?

- A prolonged conflict of enormous scale and scope

- … with mass casualties and destruction

- … with a giant impact, shaping geopolitics, economics, and international relations

- … involving major powers

- … rooted in historical, social and political ideologies

If these are the characteristics of a World War, then we need new terminology because they are also the characteristics of what we can expect to encounter, globally, as a result of climate change alone, not to mention the other dimensions of the polycrisis. ‘World War III’ will not be characterised by missiles, but rather by migration, mortality, and mitigation of a multitude of dire consequences.

Now imagine an architect, taking everything we know, and what we can envision of the future, and condensing it all down to a matter of style.

What is the diagnosis of the state of architectural practice, after this biopsy?

Not broken, but terminally ill.

What we are seeing here is a snapshot, a biopsy of sorts, of the current state of Western civilisation; or perhaps the edges of the anticipated polycrisis.

The end of architecture

Net Zero

We are steaming headlong towards a fundamental global reset. The end of architectural practice, as we know it, is guaranteed, not because we will run out of ideas nor even because a technology or a trend will disrupt it, but because the very social and economic underpinnings that make it possible will themselves be reset and unrecognisable from what we might identify today.

Here is a not so secret fact – Net Zero is not going to happen by 2050.

#Copper - Amount needed to achieve net zero. Over the next 27 years twice as much copper will need to be produced than has been over the last 3000 years pic.twitter.com/vajVglnaZE

— Dr. Copper 🔋🌎⚡️⛏️ (@CopperBullish) March 24, 2023

Here is another – global warming is going to blast through 1.5°C and keep going, with all the devastating consequences.

We can talk about structural change all we want, but what we urgently need to talk about, is how to survive.

Four charts which describe the structural nature of the transition challenge we face as a planetary civilization.

— Indy Johar (@indy_johar) June 27, 2023

They will demand systemic transformation in how we live, what we value, what we consume and what we produce and how we produce.. pic.twitter.com/eMWRIJmkt9

Limits to growth

Now, one person’s structural problems are another person’s power edifice, that they will not demolish voluntarily. That edifice is built on a foundation that is innocent looking and even aspirational, and when looked at snapshot-style, only accounts for a small percentage of the experience of our everyday lives … growth, specifically the economic kind.

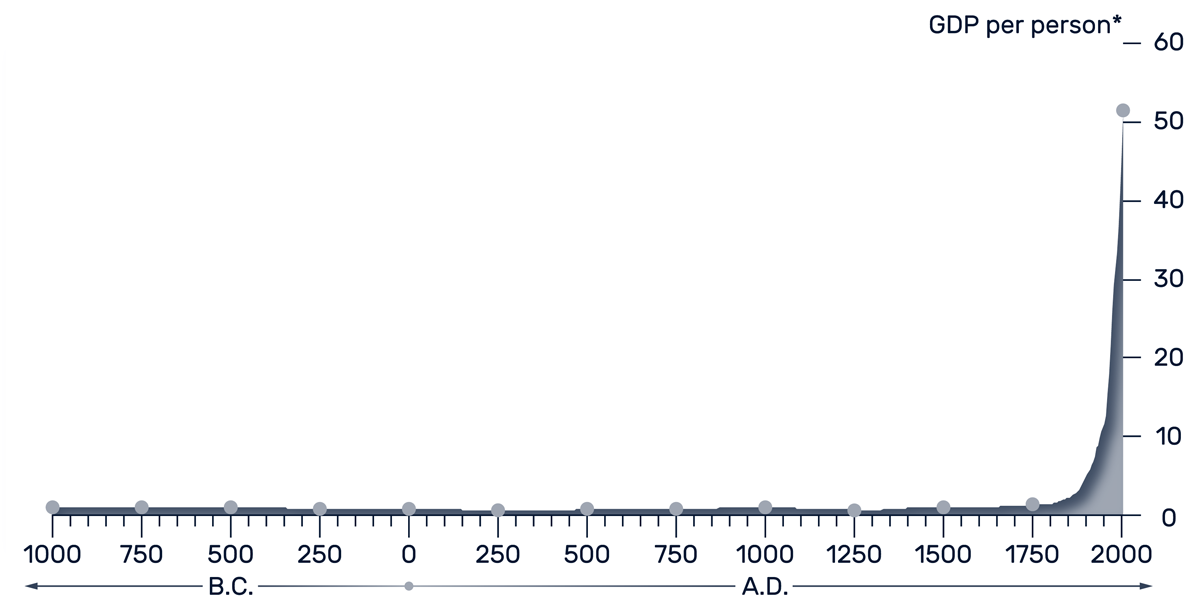

For about 3,000 years, until the dawn of the Industrial Revolution around 1750, “economic growth averaged only 0.01% per year. In other words, global living standards were essentially flat … [so that] by the year 2000, for instance, it shows that GDP per person was more than 50 times greater than three millennia before”.

The obvious fact is that unlimited growth is not possible on a finite planet. Going beyond the obvious, however, are detailed arguments for limits to growth (and degrowth) going back at least fifty years.

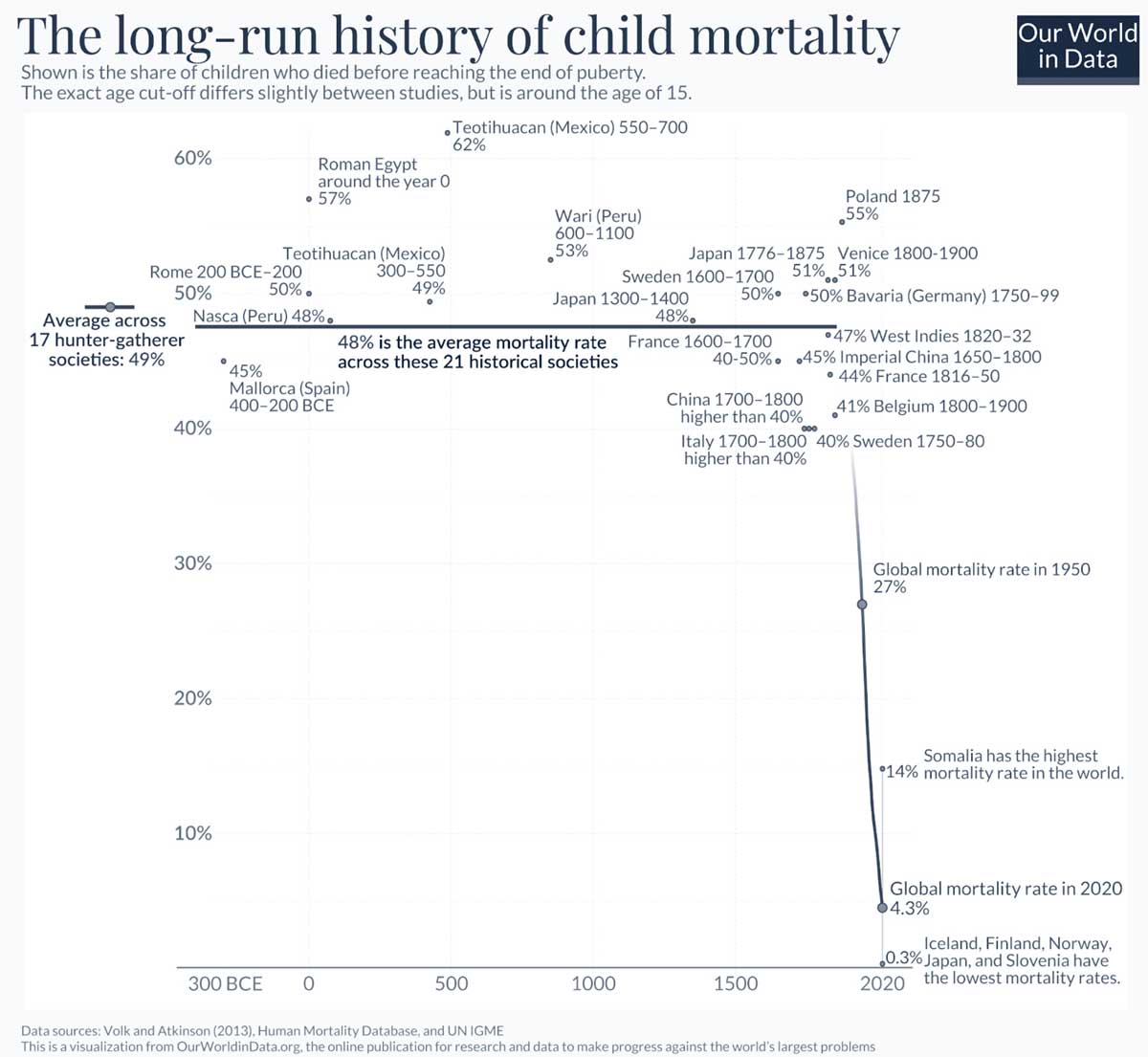

On the other side of the coin of these three millennia, we have seen a dramatic decrease in poverty and increase in quality of life globally, uneven as it may be.

Correlation does not imply causation, but undoubtedly economic growth and poverty reduction are connected, even in the context of increased inequality. Case in point, China’s ‘economic miracle’ lifted almost a billion people out of poverty. It also came at a huge environmental cost.

Nevertheless, there will always be a demand to build, but the architecture profession cannot be sustained within a product and services supply chain that is dependent on extraction of resources. As we have seen above, even so-called Net Zero aspirations are pies in the sky, far outside our capacity to achieve, and themselves demanding of physical extraction with significant human and environmental consequences.

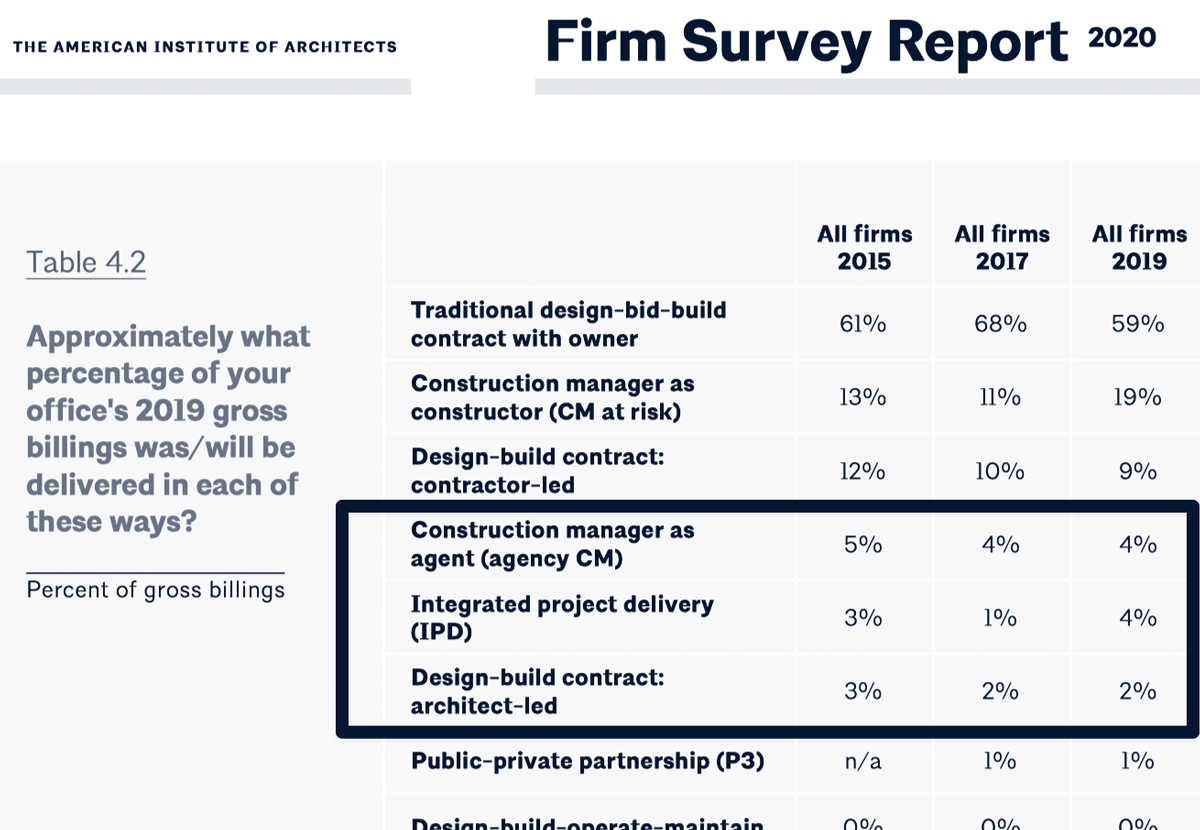

For traditional architectural practice, the biggest impediment to structural change is our place in the hierarchy of the property industry.

As you can see below, only a tiny percentage of architects have a meaningful seat at the decision-making table for the development of property.

The rest of the time, we sit near the end of a decision-making chain with little agency to have a say, at the financial modelling and briefing stage, on the big ticket items of a building’s embodied carbon footprint. With our income typically coming from professional fees rather than capital investment, it is much easier to go with the flow.

A question of class

One of the posts in this series will look at how the client-architect-builder relationship has been in a constant state of play, particularly since Victorian times. Nevertheless, the contemporary architecture professional would find a recognisable version of themselves centuries before, in the persona of Philibert Delorme (1510-70).

He envisaged “a self-governing profession of specialists with accepted standards of training and clearly defined responsibilities and privileges”. Critically, however, he emphasised the social distinction between the architect and the craftsman.

Delorme didn’t mince words, speaking of a “third class of persons … the master masons, stonecutters, and workmen whom the architect was always in control”.

The key differentiator that we project outwards to society is our role in the professions’ primary responsibility to protect public health, safety, and welfare. It is a foundation that remains, while the other distinctions are increasingly called into question.

Nevertheless, inwardly, the distinction that we lean on most today, is class. It is enabled now, as it was in the past, by patronage from those even higher up on the social ladder.

Contradicting this, in David Maister’s brutal assessment: “Increasingly, through their own actions, architects are running the risk of being treated as design subcontractors. Rather than being a spouse, many architects are becoming like the household chef, respected for technical and artistic talents, but nevertheless part of the downstairs kitchen staff and paid accordingly”.

Architects are not artists.

Architects are not, by default, gentlemen nor ladies.

Architects are the help.

More appropriately stated, architects today are workers, and we should align our interests accordingly.

Only a tiny percentage of architects have a meaningful seat at the decision-making table for the development of property.

Crafting the art of solidarity

An organisation such as the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), or the American Institute of Architects (AIA), have their roots in the craft guilds of antiquity – fraternities, often hereditary, that served as an extended family of like-minded souls, sharing (and protecting) knowledge, resources, social connections, and ultimately crafting the art of solidarity.

In their contemporary form, they have become natural vessels for re-emphasising the social differentiation that the status of ‘professional’ requires. Even if the ARB and NCARB, in the UK and USA respectively, do the drudge work of regulation, the ‘member's club’, the source of status, and the provider of evidence via the letters after your name, remains the contemporary transformation of the guild – the Institute.

Even though the depth of fraternity may not match what would have been observed in antiquity, members still revert to those founding principles of solidarity in seeking support. This can be observed weather the Institute is making broad representations for the profession for political or economic ends, in wider society, or within the institution itself, on a subject such as wages for architectural workers.

Even if its days are numbered, traditional architectural practice will not disappear imminently. So institutes will have key roles to play for some time.

Transition is the key for the Institute:

- To proactively support the development of alternative modes of practice

- To broaden the socio-economic footprint of architectural (spatial) practice, whatever form it takes, with a consequential broadening of demographics

- And perhaps, rather than simply supporting the idea of unionisation, to actually become a union itself, as the Swedish Association of Architects has done

Perhaps, rather than simply supporting the idea of unionisation, Institutes should actually become unions themselves, as the Swedish Association of Architects has done.

The asshole-sucker spectrum

If you can forgive the profanity, it is used to get very specific about a key challenge that we face. Those who care the most tend to have the least power to effect the change that they envision.

Specifically, the acquisition of power, and the mechanisms to retain that power, whether political, economic, media-driven or otherwise, involve co-option by existing power structures – in a word, ‘capture’. In the West at least, power derives from winning the game of capitalism, and subsummation by its value systems.

Assholes tend to do quite well.

On the other end of the spectrum are the suckers.

we need to stop celebrating this shit pic.twitter.com/NBNg5iAecs

— Dripped Out Trade Unionists (@UnionDrip) July 8, 2023

I hesitate to pin a ‘sucker’ tag on Ms Mebane. I don’t know her, nor do I know how much personal satisfaction she may have gained over those 74 years. However, in the same period, in the US, CEO pay skyrocketed from approximately 20x the average worker to almost 400x! Have CEOs become 20x more effective at their work, or have they become twenty times more effective at controlling the narrative such that their workers don’t strike for fairer pay, or start a revolution.

The unfortunate fact is that wealth is generated and sustained by suckers. It’s just that they are typically not on the receiving end of it.

The spectrum is also there for a reason. You would be hard-pressed to find a ‘pure’ asshole or sucker. A personality, at any given time, is likely to sit somewhere on a sliding scale between the two.

As unpalatable as it may be to some, we all need to bring out our inner asshole from time to time (please don’t visualise!), not to fight fire with fire, but to hurdle over the insecurity that tends to get in the way of getting things done.

If you believe that the climate crisis is an emergency, you are right. The same applies to our economic and social crises.

In the long run, we are indeed all dead.

The time to act is now.

Own the game you want to win

Sterling advice from Chris Brogan, and relevant well beyond the boundaries of the personal development industry.

Since the turn of the millennium, the digital shifting of theinformation substructure under our feet has precipitated the disruption of creative industries far and wide, such as …

- Music with Napster

- Photography (The Chicago Sun-Times laying off its entire photography staff, or Marissa Mayer’s assertion that “there’s no such thing as professional photographers” within a week of each other)

- Warner cutting out the middleman and streaming its 2021 slate of films

- Or an uncertain future for music, again, as predicted by renowned critic Ted Gioia

Now we have large language models and diffusion image generators to contend with.

The practice of architecture will not be spared.

If, facing all the challenges mentioned, architects were to be ‘re-invented’ in the future, they might look remarkably similar to what they look like today – that is, if the task was given to those with power in society. What might 'the powerful' need? An agent to execute, in built form, their social, political and economic objectives.

We might discover an entirely different type of persona, however, if we gave the task to those away from the centres of power. They might ask, as Richard and Daniel Susskind have, “How in the future will we solve problems to which [architects] are currently our best answer?”

The latter task is the more pertinent one.

Along the way, we will have to discard our inhibitions and prejudices. We will have to co-opt, and be co-opted … tight-rope walking! We will have to engage with capitalism. In social pursuits, we will have to accept that tech, inherently, is not an enemy.

We should not be prejudiced against the pursuit of scale. We can and should use scale to act now, in small bits and a lot, towards positive ends. Furthermore, we can and should do all of this, to the greatest extent possible, on our terms.

If we are to reimagine architectural practice, we must also be prepared to sacrifice the idea of the Architect itself.

Most critically, though, any re-imagination only makes sense if it is socially relevant to the challenges of our present moment – and it must be coupled with action – to start, to do and to keep going.

—

Before jumping into the future, we will take a moment to look back.

Accordingly, the next books on our reading list are:

- Assembling the Architect (George Barnett Johnston)

- Crisis in Architecture (Malcolm MacEwen)

- Architectural Practice: A Critical View (Robert Gutman)

- Architecture Depends (Jeremy Till)

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

The future of architecture is not what you think

Follow to find out what it might look like.