Architectural Practice: A Critical View

Robert Gutman lays out ten key challenges for the architectural profession, on the cusp of the millennium, but as relevant as ever today.

This post is part of the series, Re-imagining architectural practice

A promised land

Architecture school, almost universally in the West, delivers a creeping realisation to its students that architecture, compared to other professions such as law and medicine, is not a high-paying career. Our profession shares prestige with its cousins, but its growing appeal is partly the result of the implication that as an architect, one has the opportunity for creative self-expression, while still carrying a professional title – the best of both worlds.

It is the self-expression side that the American Institute of Architects implores us to focus on, and which, the author ultimately argues, facilitates the exploitation of junior staff and inhibits the development of enduring practices, operating at scale.

For staff, this comes about because the artistic (romantic) inclination works against both the development of a more efficient division of labour within the profession (evident in law and medicine), as well as rendering unpalatable, the idea of unionisation. Today, 25 years after publication, this is beginning to change, but not by much.

For practices, the focus on individual creativity, engendered in architectural school, lends itself to practice models that reward autonomy, evidenced by the appeal of the ‘master/atelier’ model and the overwhelming majority of one-man-band and small firms in the industry. To be sure, this is not completely out of sync with the preponderance of small businesses in the economy, but Gutman argues that comprehensive practice, at scale, is the route to greater relevance in the construction industry, and for longevity of businesses as a whole.

The reality is, that in large firms in particular, staff are working “at levels below their talent and training”. This is a function of both the non-technical and incomplete nature of much of architectural education, leaving it to practice to complete, but also the reality of staff resourcing in an environment in which architectural firms are increasingly squeezed on the fees front, while having to deliver on increasingly administrative duties.

Drilling down through the layers of Gutman’s arguments, whether on firm size, breadth or specialisation, is the issue of morale. It is evident that architecture schools produce vast numbers of graduates, who are promised an ideal, which is not realised in practice.

Business, professional and economic issues aside, this is a core problem that must be addressed in order for the profession to thrive, and indeed survive.

It is evident that architecture schools produce vast numbers of graduates, who are promised an ideal, which is not realised in practice.

Historical irrelevance

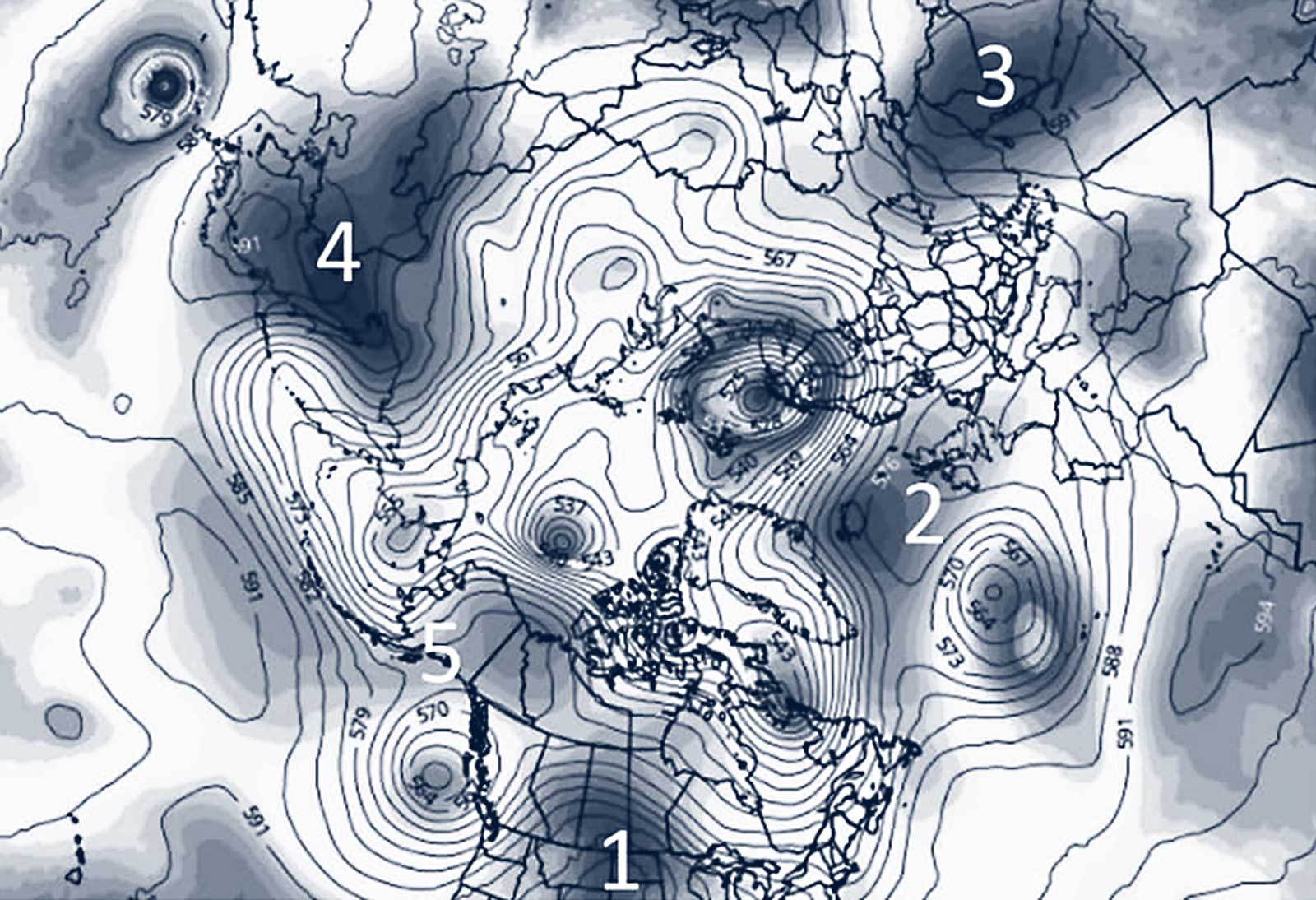

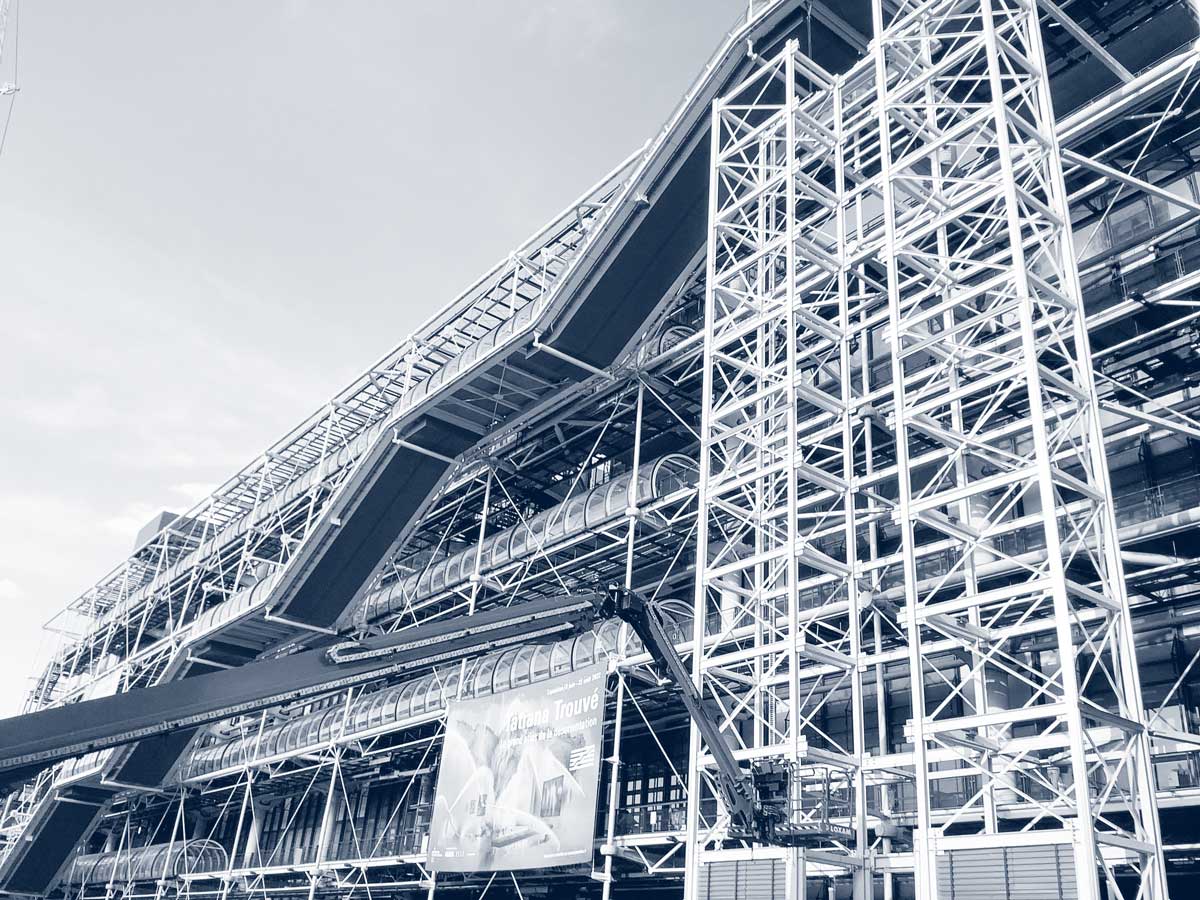

Gutman makes an interesting point about architects' increasing marginalisation within the overall building industry, as more niche specialists, as other specialisms are devolved to other professionals. One such area, relevant since the 1970s, is technology. Gutman’s point is that architects respond to their diminished role by trying to ‘re-capture’ their relevance by making "technology into a subject for aesthetic manipulation” – as in the case of British high-tech.

In more contemporary times, decades after its 1988 publication, we can observe a similar phenomenon with parametricism.

The author’s conclusion that the architectural ‘habit’ of "translating social and technical ideas into principles of form” does not do much more than boost morale and make “architectural activity appear relevant”. His implication, of course, is that this is all very hollow.

Decorator of the shed

The opposite of the trend towards specialisation is comprehensive practice, providing, in-house, the multidisciplinary requirements for realising a construction project.

It is a generalised approach which remains unfashionable today among the more design-minded firms. Indeed, the use of executive architects/architects of record is now institutionalised in the profession, particularly with architects working across borders, in geographical settings where they have been engaged for their internationally transferable visual signature, and where local technical knowledge is required, behind-the-scenes, to make it happen. In David Maister’s brutal assessment, “increasingly, through their own actions, architects are running the risk of being treated as design subcontractors. Rather than being a spouse, many architects are becoming like the household chef, respected for technical and artistic talents, but nevertheless part of the downstairs kitchen staff and paid accordingly”.

We have looked at an adjacent issue before, the matter of strategic design, addressing the fact that architects are typically brought in when vastly all the critical decisions have already been made. In the words of an executive of Century Corporation, “We’ve done so many large office buildings, we’re able to make 90% of the decisions before the architect draws a line”.

Gutman rightly sees the architect’s narrow role as decorator-of-the-shed, divorced from the process of building, as a threat to the profession; particularly since this goes hand-in-hand with the implication that architects are therefore not competent to deal with technical matters.

"Increasingly, through their own actions, architects are running the risk of being treated as design subcontractors. Rather than being a spouse, many architects are becoming like the household chef, respected for technical and artistic talents, but nevertheless part of the downstairs kitchen staff and paid accordingly"

David Maister

White labels and dark kitchens

What might a future architecture profession look like? The cooking metaphor provides a clue, so we can run with it a little longer.

The food industry has seen a recent explosion of ’dark’ or ‘ghost’ kitchens – utilitarian cooking services, out of sight of customers; with no social connection to their locale; typically set up for delivery apps; and serving one or more commercial enterprises, down to menu, branding and packaging.

The principle is that, say MrBeast Burgers, need not go through the hassle and cost of setting up their own kitchens to establish a local presence or delivery area radius. They only need to ‘subscribe’ to a kitchen system, input their corporate formulas and let the ‘ghosts’ do the rest.

The concept of architects, as the downstairs kitchen staff, or the house chef, at least assumes the individual holding a privileged, professional role with a modicum of respect and individual identity. In the ghost kitchen model, their activities can be stripped to the bone, to provide the essentials (only) of regulatory and technical coordination, in the background. In this scenario, a mass of architects would not have a name, much less a face. This is in stark contrast to the big-tent idea of comprehensive practice, advocated by the AIA, and indeed the author himself.

We have, as a profession, by ourselves, cultured generations of young architectural staff to expect to be exploited – in the past and present, not in some theoretical, future dystopia. So they are primed for work in ghost practices. We also, already have architects providing white-label services in-house, on the client side, for property developers, interior designers, government organisations and the like, not to mention the executive architects (architects of record) previously referred to, doing the same, behind the scenes, for other architects.

A ghost kitchen style practice is simply a hyper-capitalist model on the other side of the coin. It’s not so much whether ghost practices are a possible reality, but how quickly that reality will come to pass.

Here is a business idea for a generative AI entrepreneur. Why not build an app with the ability to deliver multiple creative options at speed to users, hire a celebrity as a ‘front’, and support it all with a ghost architectural practice in the background?

MrBeast Architecture?

Now imagine a scenario further into the future where technological unemployment has taken hold. A generation of architects looks back, perhaps with a hint of nostalgia, at the morsels that were at least provided to them in ghost practices. Imagine, that ghost practices, with their regulatory and technical focus, were only staffed by architects and other support staff for as long as humans could do the job better than machines.

As the generative AI revolution in machine learning has shown us, any human activity that a system can be trained on, can be simulated by those machines with rapidly increasing degrees of sophistication.

Ah, finally, we have been replaced, team. 🥲 https://t.co/sZu7RXjdSC

— Kat Dovjenko AIA (@katdov) September 5, 2022

Humans use technology today as an amplifier, magnifying their reach and productivity in ways unimaginable even a few decades ago. Eventually, when human beings become redundant in the technical/regulatory equation, perhaps then, architecture as we know it will receive its coup de grâce.

10 trends

As with McEwen, 17 years previously, Gutman frames his arguments under a number of key headings. Unlike McEwen’s outright advice, Gutman identifies 10 trends "that have been transforming the subjective experiences of Architects". Is also worth them in full:

- The expanding demand for architectural services

- Changes in the structure of the demand

- The oversupply, or potential oversupply, of entrants into the profession

- The increase in size and complexity of buildings

- The consolidation and professionalisation of the construction industry

- The greater rationality and sophistication of client organisations

- The more intense competition between architects and other professions

- The greater competition within the profession

- The continuing economic difficulties of practice

- The changing expectations of architecture among the public

And if we were to boil down Gutman’s overarching advice into one sentence, it would be that architectural practices should be bigger and provide comprehensive services. Scale and sophistication address, to some extent, all of the above trends. For traditional architectural practice, these are the qualities of the players that will hold on the longest.

Author: Robert Gutman

Year of Publication: 1996

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.