Spatial Agency

Awan, Schneider and Till lay the groundwork for another way of doing architecture

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, Space Craft

Space is indeed political

Theme, as screenwriters define it, is one of my favourite topics because it goes to the heart of identifying the writer’s values – what ’the moral of the story’ is. The closest equivalent in academia is thesis.

The authors’ theme here is that the production of space is a political act, and that what separates spatial agency from traditional notions of architecture is that it is driven by transformational intent.

Transformation demands drilling down into the mechanics of that production, deeper than matters of form, into the how’s and why’s of that spatial production. What is encountered there is inevitably both political and economic – the driving forces behind the motivations to produce, in the traditionally procured built environment.

The authors castigate architects for sidestepping these fundamentals and rightly, themselves, keep them front and centre.

Spatial agency implies an active rather than a passive outlook.

The traditional architect is primarily a passive observer to the process of development. Before they have been hired, most of the critical decisions have already been made, by lawmakers, bankers, and clients. Their job typically entails going with the political-economic flow, leaving little room for genuine transformation. Genuine power to transform lies with the landowner and financier.

It should come as no surprise then that architects remain so preoccupied with the little that is left – superficially, ‘design’. Architectural transformations are measured in primarily formalistic isms rather than with the yardsticks of social impact – unglamorous dimensions such as land tenure, access to safe drinking water, or indeed personal and community agency within the dominant power structures. Architecture sits at the end of the tail, most certainly wagged by the dog. Spatial agency, taken to its logical conclusion, starts at the tail and not only wags the dog but offers the opportunity to be the dog itself.

The politics of space captures all layers of life, not just so-called high art or elitist notions of existence. Genuine transformation engages all of these layers and is necessarily broad, collaborative, and inclusive. Spatial agency makes structural demands on the producers of space, to take the correct posture, to release the transformative potential present in their time and place.

Spatial agency, taken to its logical conclusion, starts at the tail and not only wags the dog but offers the opportunity to be the dog itself.

Words matter

Systems thinking

Architecturally trained, multi-hyphenate fashion designer, the late Virgil Abloh, infamously claimed that the foundation of his enormous success at French luxury group LVMH could be found in his 3% rule. This was his assertion, that he need only change a fashion object (or any other object) by 3% to alter its conceptual nature. In other words, he tweaks it. But that is not all, of course. He and his corporate masters, with the benefit of a track record, built a targeted marketing strategy around those small changes. It was a system.

In similar fashion, if you can forgive the pun, architecturally trained Buckminster Fuller advocated for the discovery and use of trim tabs in effecting change. A trim tab is a miniature rudder attached to the full-size rudder, which itself is attached to the rear of a sailing vessel or aircraft.

Adjustments in the tiny trim tab facilitate the movement of the larger rudder which turns the entire vessel - a very small tail wagging a very large dog.

Or the finding that political change does not need a wholesale change of thinking within a population, but has always succeeded where only 3.5% of the population are actively involved in agitating for that change.

These small percentages are not accidents. When we look at the phenomena that they are applied to – systems - we recognise what famed systems thinker and environmentalist Donella Meadows referred to as leverage points. We should not be surprised that a small adjustment can effect change, but we can note her observation that small changes, applied to the leverage points of a system, can have surprisingly large effects.

Architectural systems

Awan, Schneider and Till may not be believers. At the very outset, they carry out a wholesale clear-out of all recognisable terms:

- From ‘architectural’ to spatial

- The banishment of the words ‘alternative’ and ‘practice’

- The introduction of the word ‘agency’

- … and finally give us a new name for creative practices (sorry), Spatial Agency.

In each case, for each word, their reasoning is sound and convincing. The overall result though is alien. It is a difficult start and the term faces an uphill struggle to endure. It is certainly not a single digit percentage change to what we might consider labelling a space and place-making craft. An academic might appreciate the unveiling of this new definition, but outside this niche audience we are deprived of familiar reference points.

How might the word architecture, in the hands of Abloh, Fuller or Meadows, have been transformed or re-appropriated?

Words matter.

The authors, to be certain, have made that clear. However, the power of their new words is immediately blunted by the unfamiliarity of wholesale change. Perhaps a huge marketing campaign might have helped, but that is not the world that we are inhabiting here. Spatial agency is one of those terms that will immediately have to be explained after being uttered or written.

Frozen music

Leaning in

Typically, in producing media content, whether written, spoken or visual, or indeed spatial, we re-refine as we develop, through a process of internal and external critique – in short, editing.

Editing is not simply a process of cutting away fat, but honing the message according to a particular theme, such that each sentence, or each frame plays an active and non-redundant role in delivering the message of that theme. Typically, we are left with less than what we started with, and a more refined version of whatever is left.

The role of the critic is, in a way, that of a post-publication editor. What is it about? What might have been? What was missing? It is more common to encounter a criticism that a book, musical album, or film is too long rather than too short.

The authors here have divided the book into an initial 25% or so of argument, with the latter primarily project examples. It is a typical format for architectural monograph style books, and to the authors’ credit, and by the very nature of their arguments, they have avoided being seduced by the ’heroic’ in the latter 3/4.

Their arguments, set out in the initial 1/4 are strong and, unlike most criticism of media content, this section is too short.

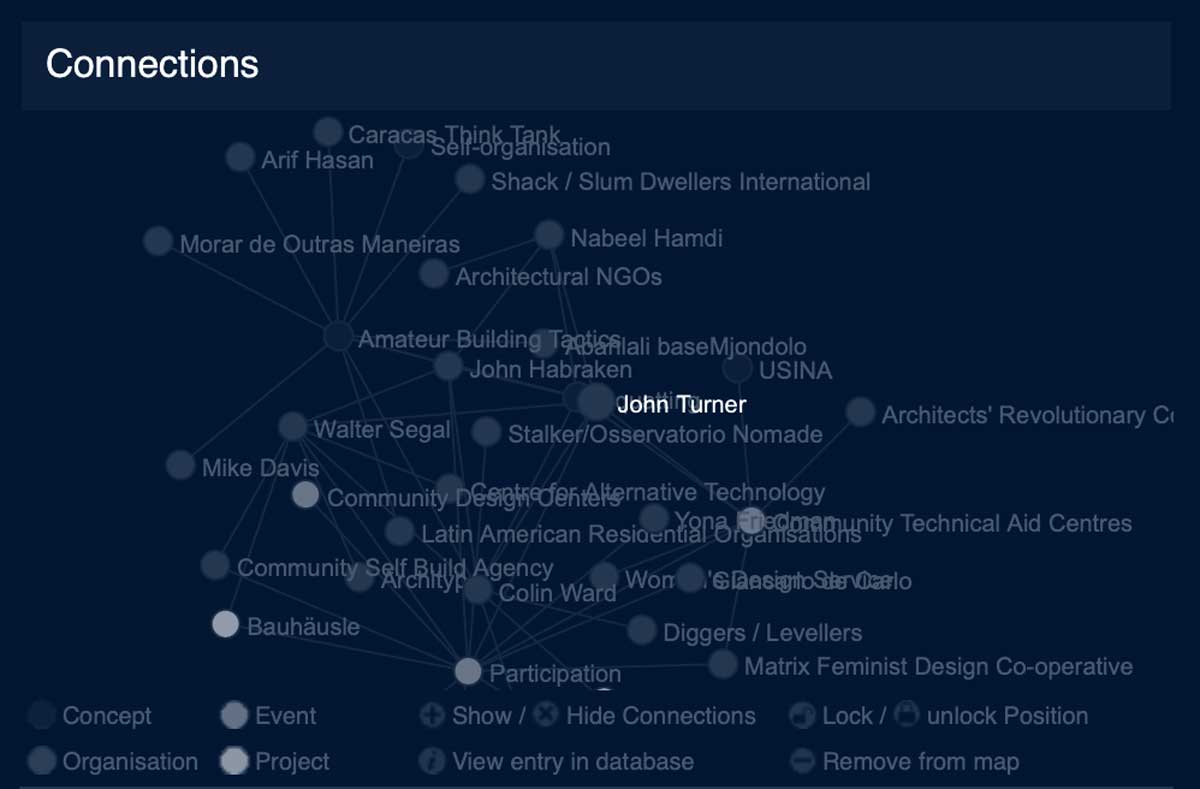

Connections

Despite the rest of their word clear-out, Till and co are sitting on a goldmine with the word ‘agency’. Through interrogating this word, they have uncovered insights that define our key challenges in the 21st-century …

- In its relationship to Actor Network Theory, its systems-based framing of our relationship to our surroundings

- In mutual knowledge, the interchange of living information among individuals and groups, not in thrall to the class-based preoccupations of ‘professionalism’.

- In the intentionality of agency itself, the “ability of the individual to act independently of the constraining structures of society”, and to negotiate “existing conditions to partially reform them” … or choose not to act.

And on and on.

The Introduction alone, merely nine pages, is worthy of an entire book. That book, of course, is the other 200-odd pages of Spatial Agency, but the introduction captures something elusive that leaves us wanting more.

The Introduction is a launchpad, a collection of living thought, stimulating line by line, ready to send the reader off in multiple interrogative directions. It is a process that has somehow become frozen in the book.

It is interesting to note that Spatial Agency started its public life as a conference, and then a website – two formats with great potential for living information exchanges. Most of the book is taken up with project examples, for which the authors, with great equivocation, justify omissions and inclusions. Spatial Agency, as a living format, is begging to carry on. And perhaps the authors struggled with this, as their format of hyperlink style references back to other areas of the book shows. These paragraphs are begging to be presented in a more dynamic format.

It might have been interesting for the book, conceptually, to stand as a ‘brochure’ (yes, that sounds a bit crude), for the more dynamic format such as the website, pushing the reader there, or even to a series of filmed documentaries.

Unlike the default mode of architectural press, which excises people from the story in favour of ‘clean’ architectural spaces, the stories of spatial agency are relatable, human stories, with which the public at large may empathise. There are unrealised opportunities here.

Emergence

Through a different frame, the Introduction is a procedural - conceptually an algorithmic engine, which can be run over and over again, across time and place, to deliver stimulating results.

Within this frame, the projects are emergents – snapshots, frozen in time, of what those algorithms might produce.

We need to go back to the procedural and bring it back to life.

Spatial Agency should have been the most important book architectural book of the 21st-century. It certainly started that way, but, somehow, with its worthy database format, it has stopped itself dead.

Agency implies intent, which is a precursor to action. Till and co have given us the engine to move forward, but they have taken away the keys.

Agency implies intent, which is a precursor to action. Till and co have given us the engine to move forward, but they have taken away the keys.

Sound Building

Changing the world

Where do we place Awan, Schneider and Till, within the canon of architectural thinking? Or specifically, where do we place their book?

As lofty and perhaps pretentious as this question may sound, it is a relevant one, because of the extraordinary transformative potential that its publication represented – timed both in the early days of a new century and so soon after the global financial collapse of 2007/8. Spatial Agency was poised to question much of what had been taken for granted.

Despite the brevity of the opening section of the book, the authors have gone to great lengths to define ‘spatial’, ‘agency’, the reasoning behind the discarding of other potential terms, and of course ‘spatial agency’ itself. My frustration with this term, having lost its living nature, is perhaps because the book begins as a call to arms but, looking back, sits more as an archive of possible alternative values.

Nevertheless, it gives us the ability to recognise and emulate further manifestations of spatial agency. This, to be sure, is enough. My disappointment is rooted in the failure of this value system to have proved world changing, when, of course, it need not have been. Nevertheless, its transformative potential, as a rallying call, remains.

Social transformation

Author Andrew Saint, and his book The Image of the Architect (1983), charted the history of the role and the perception of the architect over the centuries.

As he brings the book to a close, he faces up to the potential reality of a smaller profession, with a much reduced degree of real-world influence and imaginative potential, calling into question the profession’s very future: "Finally, can architecture survive as a special and unique profession if the ‘imaginative’ element is curbed? That is only possible if some such goal as ‘sound building’, in itself an uncharismatic target, can be raised to the level of ideology still enjoyed in schools by the endless debate about styles”.

The sound building that he was referring to, represented values that John Ruskin prized and sought to achieve in architecture. Ruskin’s value system was wrapped up in a personal ideology with a relationship to craft, religion, and aesthetics - unglamorous, yet wholesome.

Saint reminds us of some qualities of sound building:

- Simplicity and economy

- Respect for client and user

- Knowledge of techniques and materials

- With a further reminder, that collaboration was central to the idea of the sound building

He foresaw that at an inheritance of the ideals of sound building would involve technological undertakings.

Perhaps, however, the undertakings are social.

Perhaps, the inheritance of sound building is to be found in spatial agency. Coincidentally or not, this is, too, an ‘uncharismatic’ goal, but one grounded in a socially useful value system. This is the region in which the world-changing potential of spatial agency lies, at least within the context of the built environment.

He foresaw that at an inheritance of Ruskin’s ideals of sound building would involve technological undertakings. Perhaps, however, the undertakings are social.

Enclosure

The tentacles of neoliberalism have spread into all dimensions of society, not least architecture and the built environment, which are ultimately (only) clothing thrown on to financial–political bodies. The dynamics of political economy in the 21st-century are trending in the direction of a new era of enclosure …

- Of physical space (for example, with increasing proportions of privately owned public spaces)

- Of thought (with an increasingly narrow and monopolised media landscape)

- Of life and health (monopolies again, with a mere handful of multinationals controlling the production and distribution of food and pharmaceuticals across the globe)

- Not to mention the financial industry (with truly giant organisations managing values of assets comparable to mid-size countries - way too big to fail).

In this landscape, enclosure is a problem. As such, agency is a solution. In the built environment, the solution, specifically, is spatial agency.

Spatial Agency is an attempt to solve the social contradictions inherent in the profession of architecture:

- A class-based title and status, but to transcend class

- A professional and entrepreneurial arc favouring the already well-off, but to appeal to all

- A protectionist construction industry, but to deliver agency to the everyday dweller and worker.

These contradictions, within the socio-cultural frame of ‘professionalism’, are unsolvable – but only within this frame.

In this landscape, enclosure is a problem. As such, agency is a solution. In the built environment, the solution, specifically, is spatial agency.

De-professionalisation

There are hints that the profession of architecture can be absolved of its sins of conspiracy with the worst of capitalism. The authors give clues for a way out: Michelle Provost’s suggestion “that architectural significance and relevance are inversely proportional to the visibility of architecture or the conspicuousness of the architectural image”; or the authors’ own assertion that "the architect can operate modesty and invisibly, but to great effect, through an intelligent and imaginative engagement with the production with the economic, social and political contexts of spatial production, and that it is here that the architect regains a prominent role, and with it a social significance”.

These are dabblings with de-professionalisation … but the Rubicon is not crossed.

The authors remain protective of the title and identity of Architect. Curiously, most of the internal contradictions in traditional professional practice are solved, at a stroke, by de-professionalising the architect.

Most of the internal contradictions in traditional professional practice are solved, at a stroke, by de-professionalising the architect.

The true potential of spatial agency

Awan, Schneider and Till assert that “The key political responsibility of the architect lies not in the refinement of the building as static visual commodity, but as a contributor to the creation of empowering spatial, and hence social, relationships in the name of others”.

They could have gone further to say that the key political responsibility of the architect is to empower their local communities with agency in the everyday production of space, without the need for ‘professional’ intermediaries, thereby making themselves redundant.

Herein lies its world-changing potential.

Authors: Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider, Jeremy Till

Year of Publication: 2011

Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

The future of architecture is not what you think

Follow to find out what it might look like.