The Spatial Web

How the convergence of exponential technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain and extended reality, will manifest as a transformational, spatial network.

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, Space Craft

1, 2, 3, contact

There have been many claims for the title Web 3.0. If Web 1.0 was the original internet, a static, read-only but, granted, global resource; and 2.0, in short, the user-generated web; various camps have been scrambling to claim the ‘3.0’ moniker.

We have the inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee and his semantic web, a boundaryless, universally machine-readable internet where all digital information is genuinely connected, and infused with rich meaning, which itself is readable. We have crypto and its shortened ’web3’, disintermediating centralised commercial powers, servers and even money suppliers, empowering individuals, and enabled by blockchain technologies. Lastly, we have the spatial web.

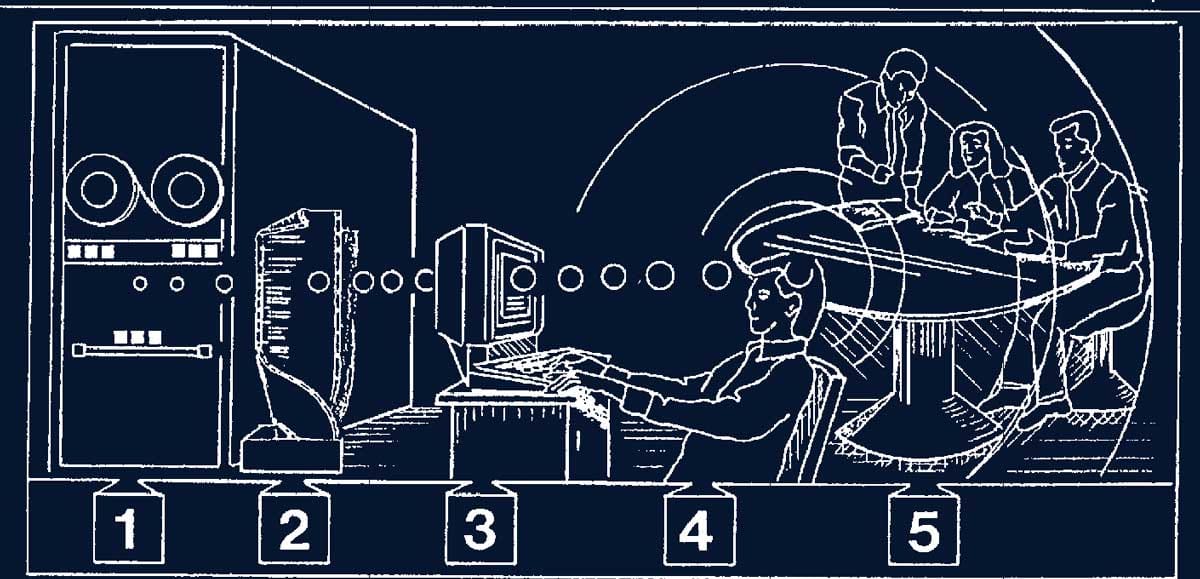

This third ‘3.0’ is less ideological and more embracing, and, in its own way, claims that all versions are correct, but not exclusive. It gives a further extension of Jonathan Grudin’s image of computers reaching out into the world – a vision of not just of an internet on screen or an internet of things (IoT), but, to quote the authors, an Internet of Everything, in which past and future technologies are integrated into a seamless, three-dimensional, real-world, whole. The authors call this new, techno-spatial reality, the convergence, or more specifically, The Spatial Web.

A common theme running through all versions of a web 3.0 is decentralisation. The semantic web breaks down barriers, the crypto bros scream “decentralisation” from the rooftops, and the spatial web evangelists hark back to the innocence of the original version of a decentralised Internet.

One thing that we can be sure of, is that Web 3.0 is here, and that one way or another, each version has a claim to legitimacy, as a vision for the future.

Where the web is concerned, the third time’s the charm.

A common theme running through all versions of a web 3.0 is decentralisation. The semantic web breaks down barriers, the crypto bros scream “decentralisation” from the rooftops, and the spatial web evangelists hark back to the innocence of the original version of a decentralised Internet.

A hyperlink to everything

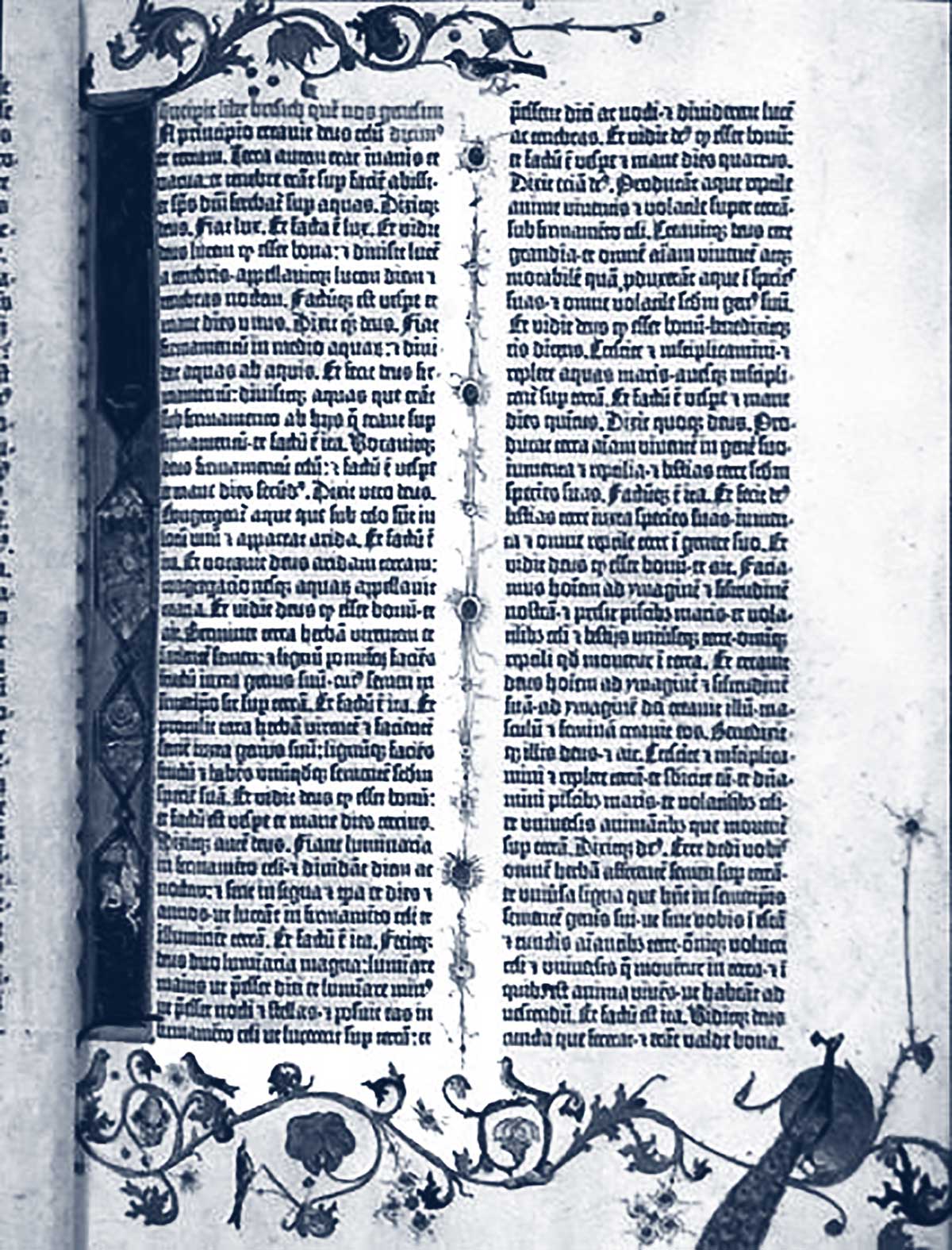

"The web was designed to be a universal space of information, so when you make a bookmark or a hypertext link, you should be able to make that link to absolutely any piece of information that can be accessed using networks. The universality is essential to the Web: it loses its power if there are certain types of things to which you can’t link.”

The words of Berners-Lee, in 1997. His paradigm was a digital library of information, shared globally through networks. This book, however, takes the spirit of the statement and applies it to the three-dimensional world.

This aspiration changes the nature, the demands, and the potential of what universal hyperlinking might engender. We are still dealing with the sharing of information, but the realm of its employment moves from communication to the experiential. This will require a new suite of protocols to turn “any space into a webspace".

The Spatial Web looks at how this might unfold, and the new threats and opportunities that arise as a result. If the authors are right, only a few decades after Berners-Lee introduced us to browsing the web, we are facing a major paradigm shift.

A spatial cycle

René and Mapes make the case for an evolutionary progression of "human interaction with information at scale". They identify a First Age with the shift from spoken language to writing; a Second Age triggered by the invention of print; and a Third Age with the invention of the screen. They map these ages on to the Agricultural, Industrial and Information Ages respectively.

It is a convenient sequence, but perhaps does not capture the entirety of the picture. Rather than looking at the sometimes abstract component, which is information, we may perceive our history differently if we look at it from the point of view of people, and their desire, rather than the informational output. From this alternative perspective, the desire is to communicate.

Before the invention of script, print, or screens we had an oral culture, which still of course exists, to some extent, in all societies. We would not be giving oral traditions their full due if we simply restricted them to the acts of speaking and hearing (or listening). We don’t need to go back in time or travel to a pre-industrial society to experience what an oral culture might have been like. We need only step outside and have a conversation with a group of friends. We would not simply observe speaking and listening, but, fundamentally, phenomena of situated communication. The simplest example is body language, which we use consciously and unconsciously to help get a point across.

So, in one simple step, communication moves beyond the limits of movement of air through our vocal cords. To get a broader point across, we may point at objects or gather them together, or draw lines in the sand — simple forms of accompanying physical representation. Together, they create effective forms of spatial communication.

Therefore, it might be fair to say that the first age was not simply oral but spatial, and that in the march through history – to the invention of script, the printing press, broadcast, and digital, we are returning to our roots. From this perspective, this is not a linear progression, but rather a cycle.

The authors give a clue to this themselves when they state that "spatial computing humanizes our relationship with information". It does so because it reduces the abstraction and the distance between what we want to communicate and what is represented. If we can point to it in the real world, either physically or digitally, then we are dealing with spatial communication.

It might be fair to say that the first age was not simply oral but spatial, and that in the march through history – to the invention of script, the printing press, broadcast, and digital, we are returning to our roots.

A luxury industry

The authors are certainly techno-optimists, and some might argue (derogatively) techno-solutionists. They foresee, breathlessly, that the future will be populated by trillions of network-enabled Internet of Things objects; will see trustless smart contracts disintermediating the legal profession; will see the dawn of quantum computing and its mind-bending potential; and all of these things will power artificial intelligence which will enhance our lives in unimaginable ways.

The idea of a convergence, involving all of these various elements, is, essentially, correct. The individual arguments put forward are not unique, and their forecast for how the multiple futuristic technologies will come together is slowly becoming something of a received wisdom – see Kevin Kelly’s mirrorworld or Ori Inbar’s AR cloud. It is safe to say that convergence is a future, but not necessarily the future.

As the authors gaze into their crystal ball, they skip over the wider challenges of society. How effective are IoT objects going to be if they are washed away with flash floods brought on by climate change? How intelligent can a system be if there is no electricity? How relevant are blockchain smart contracts going to be if they are written by those perpetuating economic inequality?

All the future technologies are possible, and indeed likely. The question is not if they will happen, but how, and for whom?

We already see the beginnings of a tech inequality. On the one hand, more than a third of the world population has never used the Internet! All of these technologies mentioned take money, and so, we can expect that they will advance, not only in countries with greater wealth, but in the subset of wealthy individuals and communities within those wealthy countries. On the other hand, we already see a backlash against extremes of tech, particularly among the very wealthy. Why are so many children of tech entrepreneurs restricted from using the very devices that their parents have made their parents wealthy? Why do ultra-exclusive, Silicon Valley schools, such as Brightworks or the Waldorf Schools, where so many of the tech elite send their children, focus so strongly on one-to-one human interaction and forbid digital devices? What do the tech elite know about tech that we don’t?

Looking at the other side of the example of teaching, we may see in the future, that state or poorer schools have no choice but to supplement a limited teaching staff with artificial intelligence learning systems. In this way, high-tech can work against the disadvantaged. Teacher shortage, no problem. Teacher strike, neutralised.

The same concept can be applied across the professions, for those seeking, say, legal or medical advice. Now and in the future, we aspire to revive human attention and engagement. Perhaps the real luxury industry in the future will be people.

Why do ultra-exclusive, Silicon Valley schools, such as Brightworks or the Waldorf Schools], where so many of the tech elite send their children, focussing so strongly on one-to-one human interaction and forbidding digital devices? What do the tech elite know about tech that we don’t?

Dystopian by default

It is interesting to see how every major iteration of the web presents tremendous potential for decentralisation, but then the very same protocols are co-opted by centralising, usually economic powers.

The DIY Web 1.0 made everyday tech enthusiasts into potential publishers, but, as human nature would have it, money came into the picture, certain winners were anointed, network effects took hold and the offline world was replicated in its power index.

Web 2.0 came along and magnified the potential for mass, user-generated content, but again, the winners such as Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, and others succumbed to the extraordinary economic power that they created, once again replicating the power index, but increasing the power inequality to near feudal levels.

The authors would have us believe that Web 3.0 will finally deliver salvation. All we can do, however, is wait to see how this too will be co-opted. Its shorter name cousin web3 started with ‘decentralisation’ written into its very foundational code, in the form of the Bitcoin white paper. Within a few years, and after the introduction of thousands of alternative coins and tokens, we observed, again, a hyper-centralisation of asset creation, ownership and ultimately wealth, this time in the shadows, in the form of venture capitalists such as a16z.

The process, optimism followed by economic realism, followed by reproduction of traditional economic hierarchies, is all but a given.

We can imagine a very graphic dystopia of the Spatial Web in the form of Keiichi Matsuda’s Hyper-Reality — an extreme layering of commercial information (opportunity) on the real world. In an unchecked Spatial Web, how far off a future reality is this hyper-reality?

Or the authors’ observation, touted as a feature, that "[t]he ability to perceive (see, hear, touch, etc) anything on the Spatial Web is determined by the permissions as defined by the Spatial Domain where a given Asset is located … If the Smart Space that an Asset is currently in is searchable, the Asset itself has to agree that based on your user permissions, you have the right to even perceive it.”

The authors precede this seemingly optimistic feature of the Spatial Web with an argument that a digital experience economy will supersede the services and offline experience economies. Now, imagine, having to pay just to browse something which you might have been able to pick up and touch in the real world. Imagine, among your friends or work colleagues, not being able to perceive objects or an experience because, say, you missed a payment on your credit card. Imagine further, with the advent of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), that if the government’s automatic debit for your speeding ticket bounces because you do not have enough money, that you are denied a whole range of social services — not just that you cannot access them, but you that you cannot see them at all.

Rather than imagining this technology or that, that can be applied to a new Spatial Web, perhaps our primary responsibility is to ensure that at least one version of this ‘third’ web remains decentralised. As author Nicholas Shaxson states, “there is no group richer and more powerful than the rich and powerful”. This is who an idealistic Spatial Web is up against.

Human ingenuity will always flower with the right incentives, particularly monetary ones. There is no risk that startling technological advancements will not be made. With this in mind, the alternative challenge is therefore not technological but social. All forms of the web are decentralised by default, but rapidly become dystopian. A Spatial Web will not be spared.

Authors: Gabriel René & Dan Mapes

Year of Publication: 2019

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

amonle Journal

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.