Spatial Practices

Reflections on architectural activism

This post is part of the series, Space Craft

Thou dost not protest enough

Critical spatial practices

What magic spell has been cast over the British public, that allows them to accept, and even encourage, change after change against their interests? Why did the French experience weeks of protest in response to the proposed raising of the retirement age to 64, while simultaneously in the UK, the British prepare to raise it to 67 with not even so much as a whimper? Why do the British not protest? Or at least, why not enough?

This book is about spatial practices, ostensibly expanding the definition of what might have otherwise been called ‘architecture’, ‘urbanism’ or other practices with traditional names. The subtext, however, is activism. Spatial practices to be certain, but at their core, critical spatial practices.

The activities so often celebrated through the book’s essays are typically anarchist or leftist in their values: DIY; temporary, atypical interventions; permanent artistically justified interventions, and the like.

Even though the last 15 years since the great financial crisis was a fertile period for reflection and activism, the needle simply has not moved. Correction, the needle has moved in the opposite direction to what much of this activism aspires to.

In the past 15 years, society has become more unequal; our public spaces have become more privatised; our media landscape more monopolised. If the proof of the pudding is in the eating, the spatial practices value system is leaving us with crumbs. This is not for wont of trying by the many contributors identified in this book. Somehow, however, they/we have not been able to break down the power structures that perpetuate the problems that they identify, and, while trying, the same structures have become even more entrenched and more powerful.

This book is about spatial practices, ostensibly expanding the definition of what might have otherwise been called ‘architecture’, ‘urbanism’ or other practices with traditional names. The subtext, however, is activism.

Orange

Spatial Practices ... https://t.co/eYIi75r3qR

— amonle (@amonle) July 25, 2023

Despite British passivity, we are experiencing a minor ‘orange revolution’. Just Stop Oil is probably the most effective spatial practitioner operating today. I would theorise that the principal source of British passivity is a media landscape compliant to the will of the powers that be, without a strong counter-narrative. Just Stop Oil co-opts this very media infrastructure in a playful but deadly serious way. They are derided by both major political parties, which provides the strongest clue that they are on to something, because both of these parties answer to the old or new establishment.

If 30,000 pages from the IPCC are correct, and who am I as a non-scientist to contradict them, then the orange paint or confetti of Just Stop Oil is mild. Compare that to the scale of the protests in France against the raising of the retirement age. Compare to the prospect of social and economic collapse that could come about as a direct result of climate change in the coming decades. Compare, unfortunately, to the intellectualised spatial practices of so many in this book.

We need to take a root and branch approach to reassessing how spatial practices might actually be effective. This starts with funding. Perhaps we have a culture in non-traditional spatial practices now where, through the grant system, we have just enough activity to give a sense that change is coming, but, in reality, not nearly enough to effect that change. If you are sitting in a seminar where everyone around you is nodding their head and feeling transformative, you are probably not going anywhere.

If it takes £1 million pounds worth of resource and people to raise £1 million pounds, we are just standing still, and in the current climate it’s actually a step backwards, making us even less able to tilt towards the scale of what’s needed. I’m sure people who deal with…

— Imandeep Kaur (@ImmyKaur) October 1, 2023

Climate change, economic inequality and social justice are the great challenges of our time. The likes of Lefebvre, Harvey and Davis give us, spatial practitioners, a foundation of reflective nourishment. But we must now build on it, broadly and quickly. If the medium is the message, and space is a medium of communication, then we have the opportunity to grab the 21st century modes of spatial storytelling with both hands and agitate for change. Our actions do not have to be dramatic, but they must be strategic. Just Stop Oil may be “annoying” to some, but within the realm of spatial practices today, they are leading the way.

Tip: If you are sitting in an activist seminar where everyone around you is nodding their head and feeling transformative, you are probably not going anywhere.

Code switching

Activism is not always overt. Minority and marginalised communities, through race, class or religion, become adept, through necessity, at a number of survival and thriving mechanisms.

Code switching is one such mechanism, typically employed, facing a majority culture, to minimise the attention given to your difference.

The complexities of conflicting values between what we wish to see and what we are forced to inhabit, mean that there is no ‘purism’ of thought or action. Whether pontificating about radical transformation from the relative comfort of academic tenure, or say, working with a community-based collective on the weekend while building offices for hedge funds on the weekdays, we are forced, not just to code switch, but to hold two positions at once.

Holding two positions at once

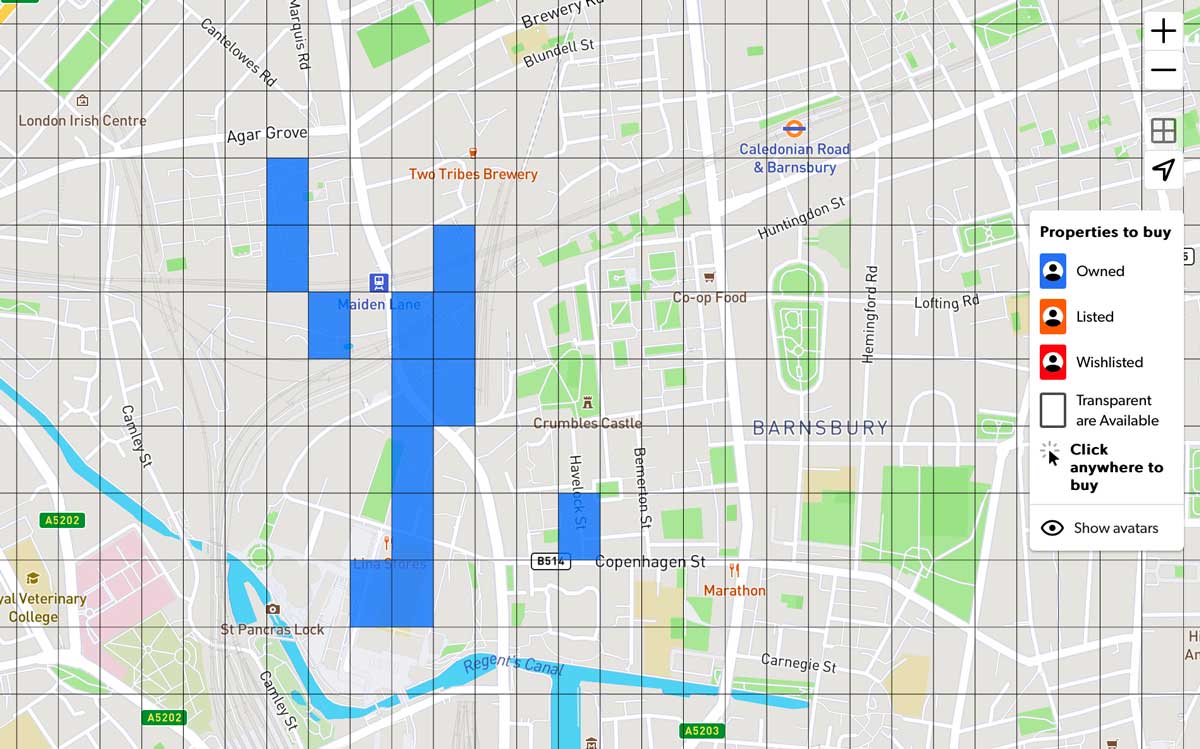

Property developers have a story to tell. It is typically one about Regeneration; about breathing life into cities; about capturing the spirit of a location, however superficially or cynically, and transforming it into a value system that you can buy your way into – and by extension, that can create commercial value for the developers themselves.

Tricia Austin has something to say about these practices. In her piece on spatial narratives, she addresses the commercial turn that so much of our urban story-making has taken.

Austin trains her bull’s-eye on property developers, but also another flavour of developer – the tech kind.

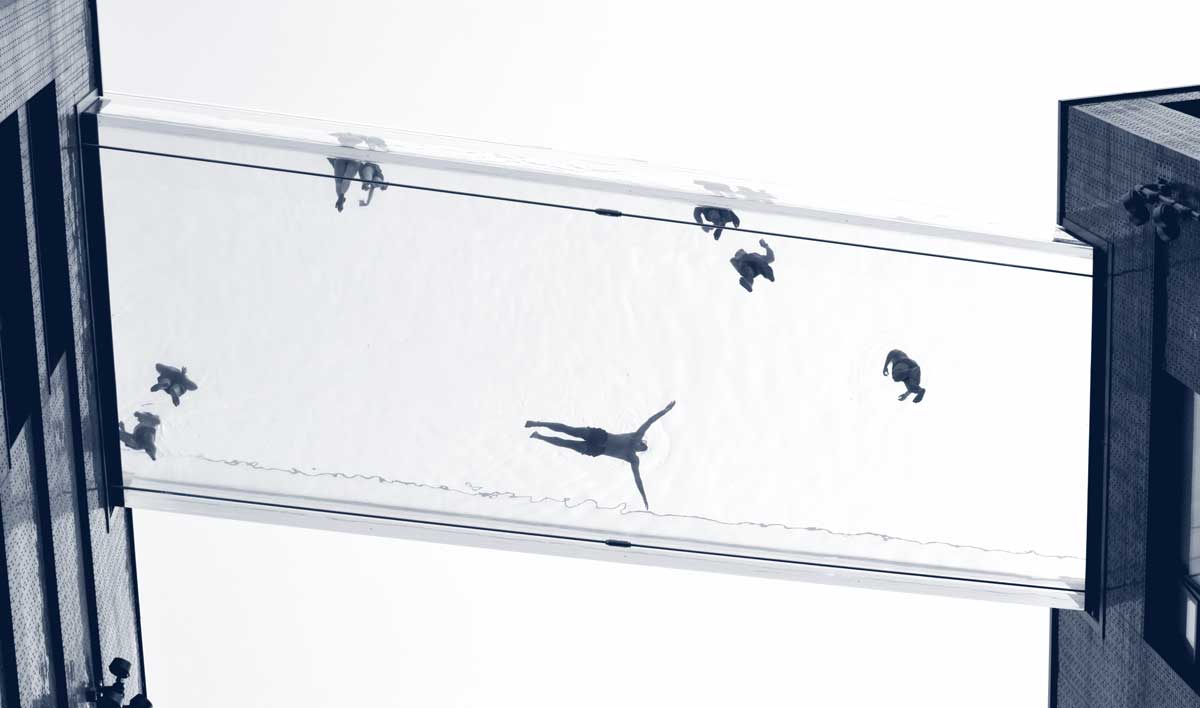

App-based augmented reality emerged in the first decade of the new millennium, bringing spatial storytelling into the digital realm. AR, in the hands of these developers, is typically of the visual kind – location-based details overlaid on images, on screen-based devices. Austin rightly highlights potential pitfalls of the use of this technology, including digital graffiti, digital trespassing and location privacy. Half a decade on from writing, these issues all remain critical.

Austin is wary of the commercial corruption of digital space as much as she is concerned about the way that this has already happened with physical space. This presents a challenge, reconciling the commercial, which she is critical of, and the activist, which she celebrates.

In the impact world, ’scale’ is a bad word. It is directly associated with speculation and extraction, at the expense of users and communities, whoever they may be. Commercial developments, whether physical or digital, typically have a higher velocity of funding because of the greater potential for financial returns. But, naturally, this speculation is accompanied by a potentially unpalatable values. Balancing inputs, outcomes, and values remains elusive.

Nevertheless, to be genuinely impactful and transformative, sustainably, narrative environments will need to simultaneously activist and commercial. It requires an outlook in which these two positions can be held at once.

So while the process of acquiring financial success, or even stability, tends to bend values away from addressing impactful values, the trick is to co-opt tech-style ‘scale’ approaches for collective action - to act now, in small bits and a lot as a way to overcome centralising, extractive tendencies. This too is ‘scale’, but of a more decentralised flavour.

Freedom and solidarity

Jeremy Till is typically brutal in his assessment of architectural education.

As elsewhere, he shines a spotlight on the structural deficiencies embodied in the totems of architectural education:

- The unit and its attendant master with a cult of personality

- The primacy of the drawing and its attendant individualism

- The crit and its attendant power dynamic

We are reminded of an educational system with rapidly spinning wheels, attached to a chassis that is standing still. The overall picture of architectural education is one riddled with failings, yet with a high enough degree of acceptance for it to perpetuate itself. We are reminded of an educational system with rapidly spinning wheels, attached to a chassis that is standing still.

Till responds with the call "to take the premises of spatial practice and reverse engineer pedagogy from them". This, he insists, will provide us with a parallel educational system to that of architecture, leaving its predecessor intact, and acting as a complimentary field of education to fill the many gaps that he takes the time to identify.

Critically, he presumes the retention of the university system, and, by implication, the retention of professional practice. Till warns, quite rightly, that "architecture education in its isolation is educating for something that is not architecture". He clarifies that this is not just a rehash of the old critique of the lack of practical transferability of much of education, but a more serious accusation – that it leaves the architectural graduate unable to imagine anything apart from the status quo.

Till, aligning with Reinier de Graf, offers a way out, suggesting that "education could be the place where we turn ‘practice itself into the object of thinking’”. This sounds a lot like an apprenticeship, but Till does not go down that seemingly obvious road.

Despite his appeal that education should provide mechanisms to break with the status quo, or that "architecture needs a real knowledge of practice if it is to produce any meaningful critique of that same practice", Till maintains a protective embrace around three status quo pre-requisites.

- First, spatial intelligence. Undoubtedly, architectural education allows its practitioners to develop a flavour of spatial intelligence. But we would have to be as isolated, as accused, to believe that architecture retains an exclusivity on this skill set. For spatial intelligence, we need go no further than any ‘vernacular’ to experience a non-professional flavour of spatial intelligence; one that the likes of Christopher Alexander, Hassan Fathy and many others, appreciative from many perspectives, might have pointed out. So architects do not have a monopoly on spatial intelligence.

- Second, the ‘freedom’ of student life – "the space to speculate unfettered by everyday demands". This is presented as an equivocation by Till, perhaps anticipating the critique that he will deny future students the opportunity to experience this halcyon era. But its contradictions are right in front of us, in black-and-white: "unfettered by everyday demands". The very source of this supposed freedom is the denial of the very contingencies that Till insists we must incorporate. This ‘freedom’ should be recognised for the extreme privilege that it is, and one perhaps that is not fit for purpose in an age of reassessment of architectural education.

- Lastly, the professional. How broad, indeed, are spatial practices? If we accept that a movement such as Just Stop Oil engages in spatial practices, then what happens if, for example, we reverse engineer their practices, as Till himself suggests as a strategy? What are we presented with? I would suggest that we are certainly not presented with a three, five or seven-year university programme. We are certainly not presented with a pedagogy laying out a runway for its graduates to take off as Victorian era style professionals. If Jeremy Till is completely honest, in reverse engineering the breadth of spatial practices, he may have to advocate for the abolition of university education entirely.

Nevertheless, Till leaves us with essential advice on how to negotiate the sometimes contradictory demands of spatial practice. In this, again with Dodd and others, he invites us to engage with both sides of the coin: detachment and engagement, freedom and solidarity.

Build it and they will become

Theory is dangerous. Architecture that lives on the page exists in a realm of possibilities that can sparkle the imagination, travelling into the farthest reaches of what might be. So often, words jump off the page with optimism. Equally, often, when theory is immediately followed by a recounting of implementation, much of the energy is lost.

The contingencies of the context – physical, economic, social and so on, bring themselves to bear on the process of transformation from theory to reality. It is a bit harsh to say that many of the project examples here are uninspiring, but that thought creeps in when I am being honest to myself.

This is an ivory tower danger that we must be wary of in the practice of architecture, and, in fact, anything that has to be ultimately realised outside cloistered walls. The more distant the journey from theory to reality, whether in time or in space, the greater the degree of energy loss.

We can therefore assume that the scenario with the least possible energy degradation is one in which theory and implementation are one and the same. The solution is to build – early and often.

Game developers are advised to play-test with external users no later than 20% into the development process. Architects, as they traditionally practise, would not be able to heed this advice, since their spatial play-test, (occupation), happens at 100%. Everything before this moment is abstract theory, even the technical elements.

So again, build early and often, and if user input has to start at 20%, that implies that the users themselves should have an active role throughout.

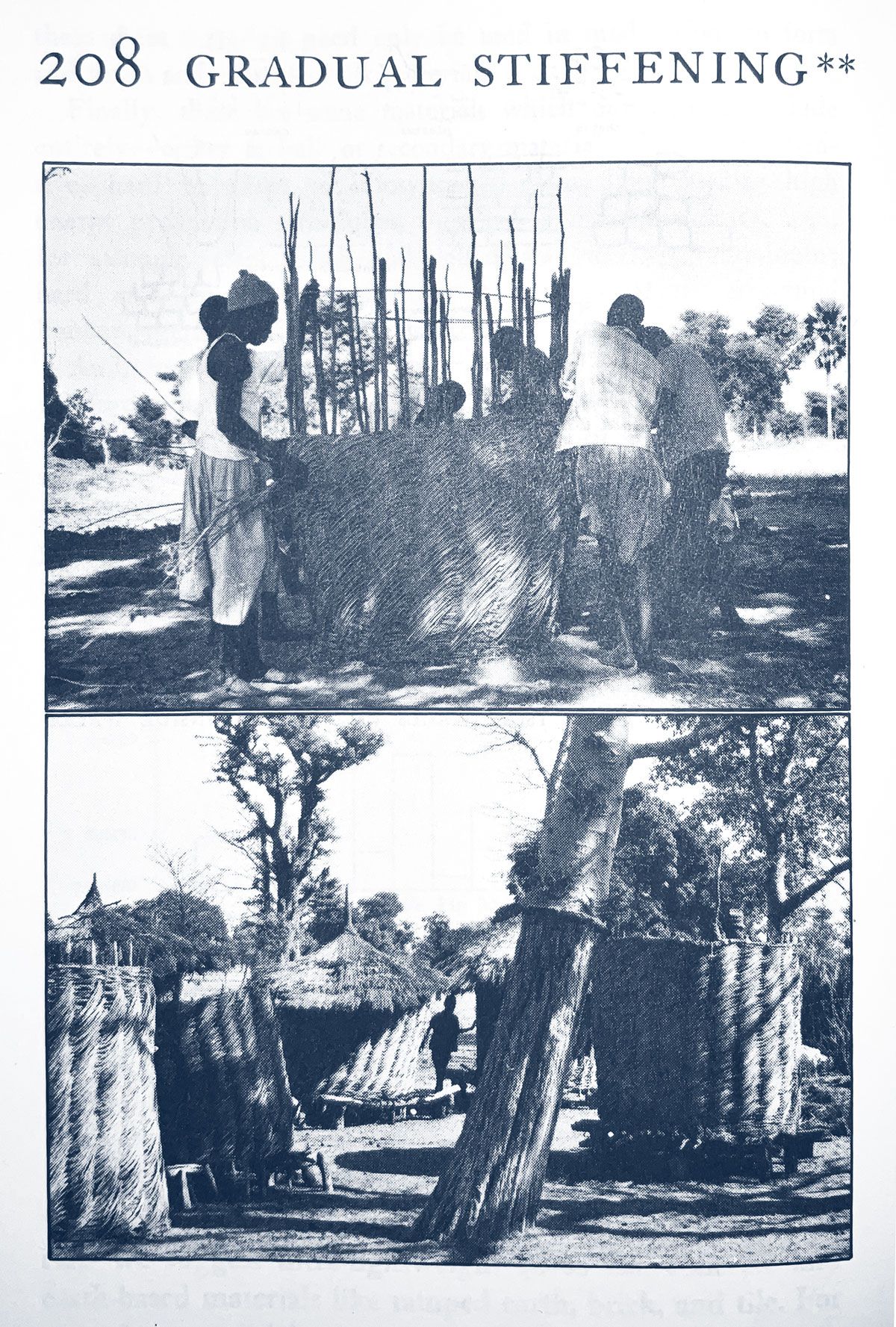

Christopher Alexander’s GRADUAL STIFFENING pattern comes to mind here, in which we start the physical and social framing of space before we have the full picture, and gradually fill it out to complete that picture. Here, building is theory.

Naturally, we cannot live in a ‘gradual’ structure without a roof, but we can physically occupy the space, collaboratively with others, as part of the process of creating that space, in situ.

If theory is a problem, building is the solution. As the tools of architectural practice evolve, perhaps some of them will include devices to make simultaneous building and theory a reality.

Build early and often, and if user input has to start at 20%, that implies that the users themselves should have an active role throughout.

Growing up

It would be interesting to publish a book like Spatial Practices which specifically excludes anyone under the age of 35.

We have spoken about ‘contingencies’, both the ‘front-of-house’ and ‘back-of-house’ varieties. Back-of-house contingencies have to do with the typically unacknowledged facets of life that impact the practice side of architecture – how to allocate your time in relation to other pursuits; how your upbringing and your network impacts your ability to build a practice in the first place; and above all, how to pay the bills.

Younger practitioners, recently graduated, are usually free of the burden of mortgage payments, challenges from the spouse to be ‘serious’, or other social or family pressures that come with the approaching of middle age years. The recently graduated may find it easier to accommodate romantic aspirations, even if these occupy the time outside a numbing 9-to-5 job. But how many of these aspirations survive life’s later demands? If you are interested in starting any kind of architectural practice, this is perhaps the most important question of all.

It is a question which we could ask of featured collective EXYZT. As interviewer Shumi Bose put it, their "architectural education gave [them] some skills that [they] could use for money. But also, some ideas that [they] can exercise, maybe not for money”.

The collective supported their ‘hacker’-style projects by working freelance for established architectural practices. As a group, they had some elements arguing that projects should not be economically driven, and other questions about whether governance should be more hierarchical or horizontal. These are foundational questions for practice, whatever form it takes, critical, if it is to endure. These are the back-of-house contingencies that too often are dealt with peripherally or only in crisis. They should be central questions.

The years between university graduation and marriage/mortgage are typically full of one thing – options. Those options narrow as soon as life’s other demands come into the frame. Individuals themselves also change quite significantly over the same period, maturing and working out ’what they want in life’, within the wider social frames. The marriage/mortgage stage of life is where so many collectives quietly withdraw from the spotlight or dissolve altogether.

Certainly, architecture is enriched by their youthful energy, but the implication, with their lack of longevity, is that they are the beneficiaries of privilege – the privilege of youth; often, in architecture, the privilege of wealth; and if not, the privilege of not having to worry about the lack of wealth. The damning conclusion is that economic and social pressures, regardless of their gravity, dominate, despite ‘alternative’ values.

Total amount of student debt in UK reaches new record of £205 billion. pic.twitter.com/ikAYBj65eF

— Matt Goodwin (@GoodwinMJ) June 15, 2023

Now, late capitalist societies, with diminishing social support, new or increasing student loan debt, and steadily increasing inequality, are shortening the period of these ‘golden years’. Perhaps, with student loans, the marriage/mortgage era has been brought forward to the day of graduation. Students may face the prospect of having no golden years at all. Therefore, we need to think more seriously about these back-of-house contingencies. How many idealistic practices will survive in this changing environment, or not be able to start at all.

A model based on privilege is not sustainable. We need a new model altogether.

Perhaps, the marriage/mortgage era has been brought forward to the day of graduation Students may face the prospect of having no golden years at all. Therefore, we need to think more seriously about these back-of-house contingencies. How many idealistic practices will survive in this changing environment, or not be able to start at all.

The future is now

The chapters of Spatial Practices are structured in a ‘last but not least’ format. The concluding three certainly give us food for thought and leave us on a note of optimism, with ideas for the future.

Situated drawing

Andreas Lang’s notion of situated drawing is fascinating, and begging to break out of the walls of academia. The practice, an improvisational manner of representation, using the context and sometimes materials of the site in question, addresses, at a stroke, so many of the aspirations of the spatial practices evangelists. At least as a teaching tool.

First and foremost, it takes the student out of the studio into the real world that they deem to make proposals for. It provides a direct incentive for students to engage with the communities where the project is cited. In the open air, so to speak, it offers a release from the hidebound values of mainstream architectural education. Lastly, from a material perspective, students are incentivised to use what is at hand, and potentially with their hands.

Public Practice

Pooja Argawal’s piece on Public Practice, now well established, takes architects away from the purely commercial into the realm of the public. This is not the landscape typically celebrated in architecture school. It does, however, embed architects closer to the site of decision-making and ultimately power, than the position they would operate from as ‘consultants’.

They operate within the framework of strategic design, closer to the brief than to the result. It is a position, simultaneously, of great learning and influence. How much more impact could an architectural practitioner have on, say, the carbon emissions of a project, at the briefing stage rather than the design/execution stage? How much less personal energy would be if expended by getting it right early rather than making it simply ‘good’ later on? How much more collaborative must we be by default when sitting among our peers but outside a purely plastic design context? If impactful design making is the question, strategic design is the answer.

Unionisation

Peggy Deamer, though evangelising for cooperatives, illuminates an under-reported limitation in architectural private practice – firm size.

92% of firms in the US have less than 20 employees. She gives us other statistics, but the key takeaway is that the high volume of smaller firman means that, by and large, the profession is unable to access economies of scale, experience corporate longevity nor compete with large multinational practices.

Her solution is cooperativisation, of the consumer, producer, and worker varieties. She is up against it. The possibilities here, as with the two other examples above, run counter to the driving forces within architectural culture. These forces will not be overthrown overnight.

Takeaway

We should note that all three approaches, immediately above, not to mention the many other examples in the book, present alternative value systems within spatial practice.

They all demonstrate that possibilities do not lie in the future, but are all here now. Dodd and her accomplices have done us a service by illuminating them.

Now to shout their stories from the rooftops, and get working on the ground.

Editor: Mel Dodd

Year of Publication: 2019

Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.