Architectural Intelligence

Architectural practitioners with a goldmine of ideas, exploited, for the most part, outside of the profession

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, The other kind of A.I.

Another Kind of A.I.

The introduction to this series was a bit of a tease.

’A.I.’ of the artificial variety is at or near the peak of its hype cycle, so it may have come as a bit of a surprise to some to find ‘Intelligence’ prefixed by ‘Architectural’.

There is a twist to the tale, however, because the architects spoken of do not leave the tech obsessed empty-handed. Quite the contrary, in fact, and it is here that our author Molly Wright Steenson shines a spotlight on a cast of architectural characters whose paths do not always cross in space or time, but certainly in theme – interactivity.

The characters, Christopher Alexander, Richard Saul Wurman, Cedric Price and their associated collectives all left their mark on the digital landscape and remain influential, beyond the field of architecture, to this day.

Limits to growth

The early days of the development of a new way of life, or technology, reveal the components of its DNA that are maintained regardless of how advanced or complex that system becomes. So, it is with the relationship between computing and architectural design.

Christopher Alexander, unusually for an architect, had degrees from Cambridge University in both architecture and mathematics. He had very early access to computers, in the 1950s and 60s, at a time when their cost was comparable to a house and their size to that of a room. In those early days, when, again unusually for an architect, Alexander was able to programme these computers, he quickly realised a fundamental limitation: "The effort to state a problem in such a way that a computer can be used to solve it, will distort your view of the problem".

Wright Steenson points out that Alexander "struggled with the limitations of his programs and tools in representing the complexity he sought to find". We now have his well-known books The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language, which were more than a decade away, and these critical publications in his personal history demonstrate something fundamental – that the ultimate ‘software’ solution to create meaningful places exists within us already. Alexander concludes, in his own way, that the complexity of computer software is insufficient to represent the complexity of the world, a world which we experience with a human body in the further complexity of nature.

By the time he gave us his two, landmark books, computers were no longer his primary tools. Design via the computer can only simulate the complexity of design in the real world, and in his view, it does so inadequately, or at least it is most useful in solving problems that are "the most trivial and the least relevant". One could argue that this is true of generative architecture, successful in form-making games and physical production, but useless in addressing the other key social aspects of place-making.

Cybernetics, often conflated with computing through the use of terms such as ‘cyberspace’, is, fundamentally, not at all to do with computing, but rather a study of matters of control. It happens to be useful for computing, but its core thesis, illuminated by Ross Ashby’s Principle of Requisite Variety, is useful in understanding Alexander. Ashby stated that, in order for a system to be stable, the number of possible states of a controlling system must be equal to or greater than the number of states of the system that it controls.

It is therefore impossible for computer software to deal with the full complexity of place. Alexander’s alternative is to use the built-in complexity of the human mind and body and integrate it seamlessly with the complexity of nature using the synthesising methods of language, as evidenced with his pattern languages.

Those observations about the limits of computing date back 60 years, but they are as relevant now as they were then.

An unruly heir

The problem with Patrik Schumacher (not included in this book) is that his outrageous statements suck all the oxygen out of the room, before you can take the time to understand how he connects supposedly superficial formalism to deep social and economic thinking.

Schumacher, like his late mentor Zaha Hadid, is a proponent of generative design, specifically ‘parametricism’ - design driven by manipulation of algorithms. An algorithm is simply a set of rules that tells a system what to do when, under which circumstances. Parametricism is akin to having a series of knobs that you can twiddle, each with a generative input, with design forms coming out the other end as output.

Though some may be horrified at the comparison, including Schumacher himself, he is the 21st century heir to Christopher Alexander. What Alexander and Wright Steenson refer to as ’generativity’, is directly related to the algorithmic thinking of Schumacher and his generative design - the notion of code applied with syntax (as in language), creating a network of sequences.

Whereas Alexander’s patterns are executed in situ, typically by hand, and processed through human values, Schumacher’s cut to the algorithmic chase and are performed purely by silicon, except for the human knob twiddling.

Alexander’s generativity is carried out with the aspiration to capture the quality that cannot be named, spiritual, deeply connected to human values and the human soul. Schumacher, on the other hand, professes to be concerned about formal possibilities. But the trick that is missed in much of the criticism of Schumacher’s thinking, is the way that he connects the social dots from this formalism to a broad spectrum of libertarian values. This, in itself is not surprising, except that those with counter-arguments are typically less effective at dot connecting.

The irony of Schumacher’s libertarianism is that it is propped up by the dominant mechanisms of corporate power and a compliant state, while those with, say, impact or community-centred values are perpetually in a mode of resistance.

In Schumacher's case, there is no conversation (back-and-forth) between the algorithmic system and human values. There is, rather, a linear route from the knob that is twiddled, to the silicon of the machine, to the formal output, to the potential for the total exclusion of human hands from subsequent manufacturing processes. Schumacher’s freedom is freedom from the messiness of humanity towards a purity of form. In contrast, Alexander’s life mission was to excavate the patterns embedded in our very humanity.

Framed through the generative lens, Schumacher is indeed Alexander’s heir, but not one that Alexander would likely have been proud of.

The thing about ideas, though, is that they have a life of their own, and neither Alexander nor we can control how and where they land or evolve.

Unruly as Schumacher may be, if we dig a little deeper we will find that the libertarian blood that runs through his veins, flows from the beating heart of Silicon Valley - the very place where Alexander himself spent his formative, Pattern Language years.

Therefore, the relationship between these two should not come as a surprise.

Though some may be horrified at the comparison, including Patrik Schumacher himself, he is the 21st century heir to Christopher Alexander.

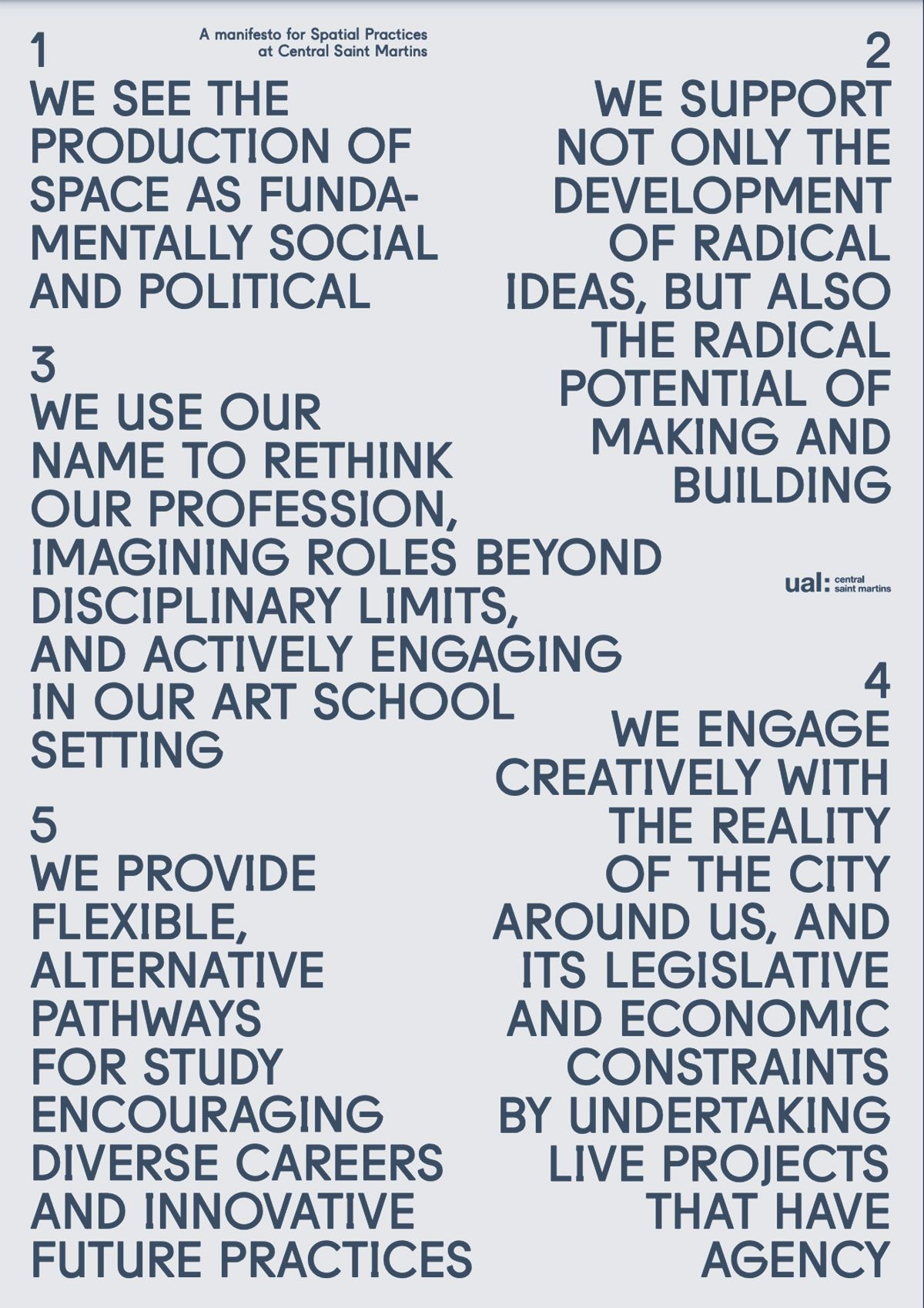

Prefix: Spatial

What is the future for the title of Architect? The experience of Information Architecture (IA) might provide a clue.

IA was part of a burgeoning collection of design practices emerging out of the digital landscape of the late 90s and early 2000s. As their titles and functions rapidly evolved to reflect the similarly evolving landscape, they identified themselves as Information Architects, User Experience Designers, differentiated between “little IA” and “big IA”, and oscillated between metaphors of ’architecture (serious, thoughtful) and ‘design’ (cool, fleeting).

At the 10th IA Summit in 2009, Jessie James Garrett attempted to settle the matter. He declared, "What is clear to me now is that there is no such thing as an information architect … there are no information architects. There are no interaction designers. There are only, and only ever have been, user experience designers".

Wright Steenson points out that even this supposedly conclusive view evolved somewhat, but its purpose was to capture the possibilities where "more could be gained by uniting forces and promoting what the umbrella of the digital design practices shared".

Architecture is not Information Architecture. The title has been around for millennia, and it could be argued that the current professional structure of practice is over 500 years old. Nevertheless, it too is subject to the evolving landscape in which it operates. Digital developments, from the web to digital twins to augmented reality and beyond, are encroaching rapidly on the ‘professional’ world of the spatial.

While, in the future, we will still have uppercase ‘A’ Architects building bricks and mortar buildings, which will always be necessary, it may be more appropriate for the profession, like IA’s, to capture a broader spectrum of practices.

Academia has already embraced the term spatial practices in this regard, and so, perhaps, the inevitable umbrella term will be spatial designer.

Wright Steenson points out that the contemporary, more closed nature of digital experiences, has resulted in a shift towards the primacy of engineering (coding) skills. The demographic that accompanies this shift is less diverse than the population at large. Similarly, the profession of architecture still struggles when it comes to diversity, with minority ethnic groups hugely underrepresented, particularly in urban areas, and the representation of women only now catching up to an acceptable 50% level.

The ‘spatial’ prefix rather than an uppercase ‘A’ architectural title suggests a de-professionalisation of roles in the built environment. This is not have to mean a dumbing down of expertise, but what it can certainly mean is a broadening of fields of expertise and, critically, also of access. In the end, titles matter.

Authority

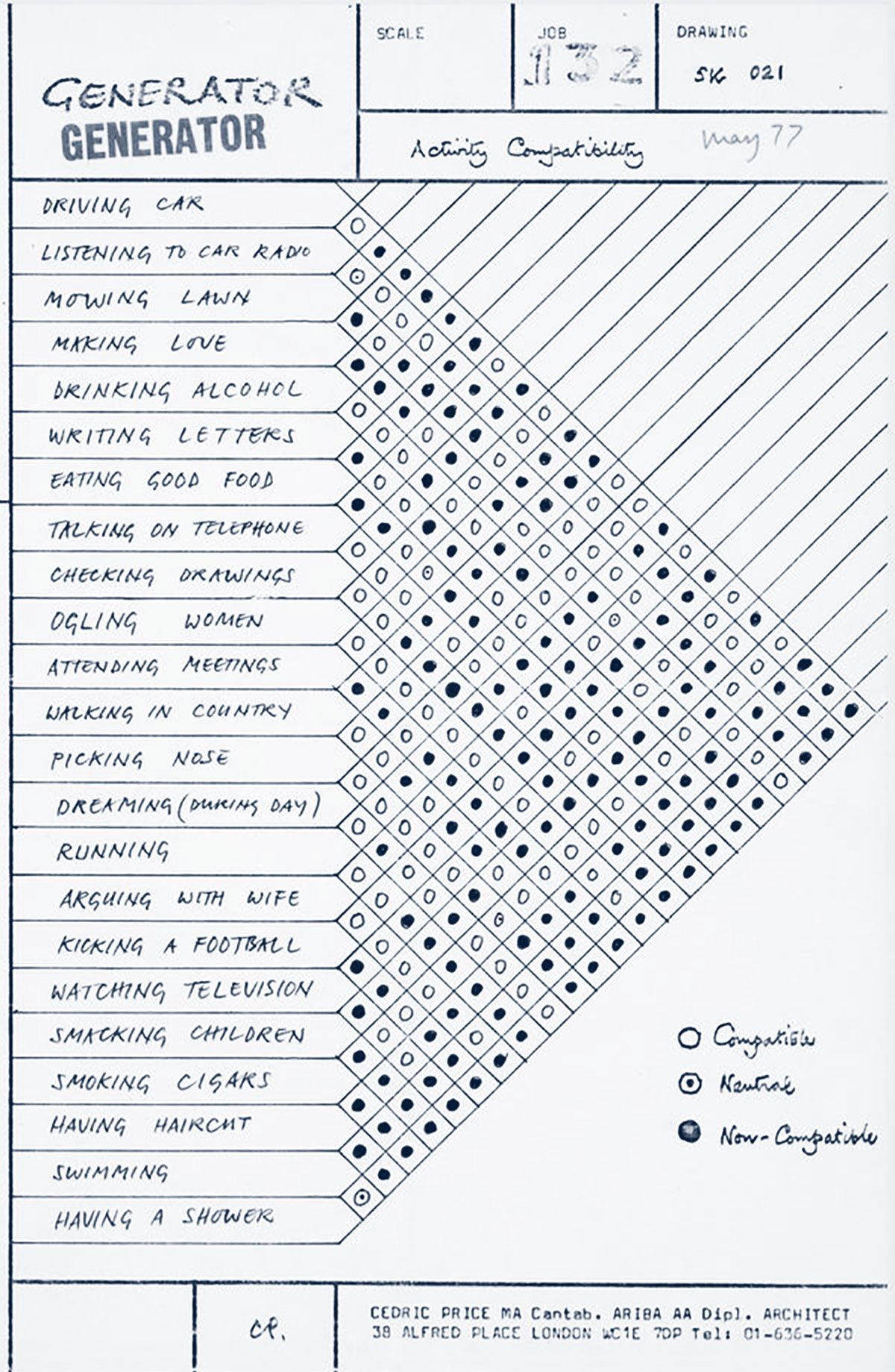

We can only marvel at the ambition and eccentricity of Cedric Price’s three landmark, but unbuilt schemes - Fun Palace, Oxford Corner House, and The Generator.

These are not simply paper architecture schemes, but ideas developed intending to realise them in true, physical form. In each case, Price had a mountain to climb. In each case, he was proposing to build a ‘walk-in computer’ – cybernetically interactive; responsive to the choices and desires of its users; physically altering the space in ways that would make a West End or Broadway set designer blush; incorporating computing, networking, electronics, and media in ways that we could possibly only observe on the newsroom floor of a major media organisation today.

How charismatic and convincing must Price have been to suggest the purchase (excluding running costs) of a computer to run the transformation of a tea house, costing roughly £15 million (about USD$19 million) in today’s money? His budget for the 10-month feasibility study was the equivalent of approximately £400,000 in today’s money.

As whimsical as the ideas were, these were not whimsical sums.

We would have to be in the room, in each case, to really understand how he pulled this off. However, we can certainly conclude that he had a solid crutch to lean on – the title of Architect.

A word in use since at least the time of the Roman Empire, the title, in its simplicity, directness and evocation of creativity, professionalism, and authority, carries weight and lends authority to those who are entitled to use it.

Today, the brand value of architecture is greater than its utilitarian value. We will examine the crisis in architecture, evident since at least the 1970s, in a future post, but, needless to say, the role of the architect, in the hierarchy of the property industry, does not live up to the authority of its brand.

Price’s title block on the Activity compatibility questionnaire for The Generator is telling. On the surface, we can read it as a traditional architectural document, complete with a title block and drawing number. If he slid it in among a pile of architectural drawings, we might not have had a second thought about it.

While the format is industry standard, and it carries the weight of a traditional architectural drawing, its content, and intent of its use, are anything but traditional.

In the lower section of the title block we have details of the author: CEDRIC PRICE MA Cantab. ARIBA AA Dipl. ARCHITECT.

- MA Cantab. = Oxbridge - elite and renowned university

- AA Dipl. = Private, elite and renowned architecture school

- ARCHITECT: Two millennia of authority behind this title

What we have here, is Cedric is Price wielding the authority of history and class as leverage to entitle himself to explore.

Today, the brand value of architecture is greater than its utilitarian value. The role of the architect, in the hierarchy of the property industry, does not live up to the authority of its brand.

3-dimensional artificial intelligence

Hype cycles are a hell of a thing!

In certain corners of the media, such as Twitter, but even in mainstream print and TV, you would be forgiven for thinking that artificial intelligence is about to take over the world.

Large language models (LLM’s) is such as ChatGPT and diffusion image generators such as Midjourney dominate the discourse. Almost everyone is skating towards the puck where it currently is.

In the background, and no less consequentially, is another major player. Apple has been quietly incorporating both language and image-based machine learning (ML) into its operating systems since at least 2017, when they introduced the neural engine with the iPhone X.

Though promoted at their developer’s conference that year, it was nevertheless a low-key revolution, not least because this processor is hidden inside a device.

What it does do, however, is dedicate a powerhouse processing unit specifically to machine learning.

Apple, unlike its LLM and image generator peers, has both feet firmly planted in the hardware realm. Its Apple Watch, iPhones, and even headphones, contain accelerometers and other sensors that monitor every dimension of movement of your body imaginable – from the blood flow in your veins to your walking, running and driving in the outside world.

The Apple Watch only sits on one wrist, but it can already approximate what the rest of your body is doing – as evidenced in its ability to automatically determine whether you’re running, cycling or even which swimming stroke you are using.

Apple is taking a different approach to artificial intelligence, which is strikingly similar to that proposed by Nicholas Negroponte and his Architecture Machine Group (AMG), 40+ years earlier.

Nicholas Negroponte’s proposed architecture machines were three-dimensional environments with sensors, feedback, and interaction with users, and, theoretically, could exist up to city scale. Where Negroponte spoke of ‘dialogue’, and its continual role in building the relationship between the user and the machine, we now use the term ‘training’ to refer to the machine learning process that takes place within large language models and diffusion image generators.

Both Negroponte and Apple were and are pursuing three-dimensional, artificial intelligence environments. The difference, now, in 2023, is that Apple has an even more intimate degree of training data than Negroponte could have imagined in the 1970s. Apple knows how long you were dreaming last night, or where you spend most of your time. It will soon know what you stare at most of the time. Where Negroponte’s imagined architecture machine builds a metamodel of itself, Apple can build a metamodel of the user. We already have the multiple sensors in its various personal devices. Now we have releases of further simulations of ourselves through technologies such as Personal Voice (which simulates your voice) and the three-dimensional avatar that the Vision Pro creates of its users.

Where Negroponte’s imagined architecture machine builds a metamodel of itself, Apple can build a metamodel of the user.

Apple, more than any other company, though not trumpeted, is in pole position to build a virtual you. This is the key difference between Apple and its rivals. Large language models and diffusion image generators create models of dialogue and visual creativity that might otherwise have come from a user. Apple, on the other hand, is building a model of the user themselves.

Negroponte’s insights, decades before we could envision the Apple technological ecosystem, are prescient: “The prime function of the machine is to learn about the user. It is to be noted that whatever knowledge the machine has of architecture will be imbedded in it; the machine will not learn about architecture. The machine will indeed build a model of the user’s new or modified habitat. But it is simultaneously building the model of the user and the model of the user’s model of it”.

Or “Does a machine have to possess a body like my own and be able to experience behaviours like my own in order to share in what we call intelligent behaviour? While it may seem absurd, I believe the answer is yes”.

These are huge insights, a lifetime ahead of their time.

What is more extraordinary, is that those corners of the media, so obsessed with the headline grabbing ChatGPT, Midjourney, and others, have not yet woken up to this spatial, three-dimensional approach.

Making a detour

One of the lessons that we can take away from Wright Steenson’s book is that architectural thinking can produce a goldmine of ideas.

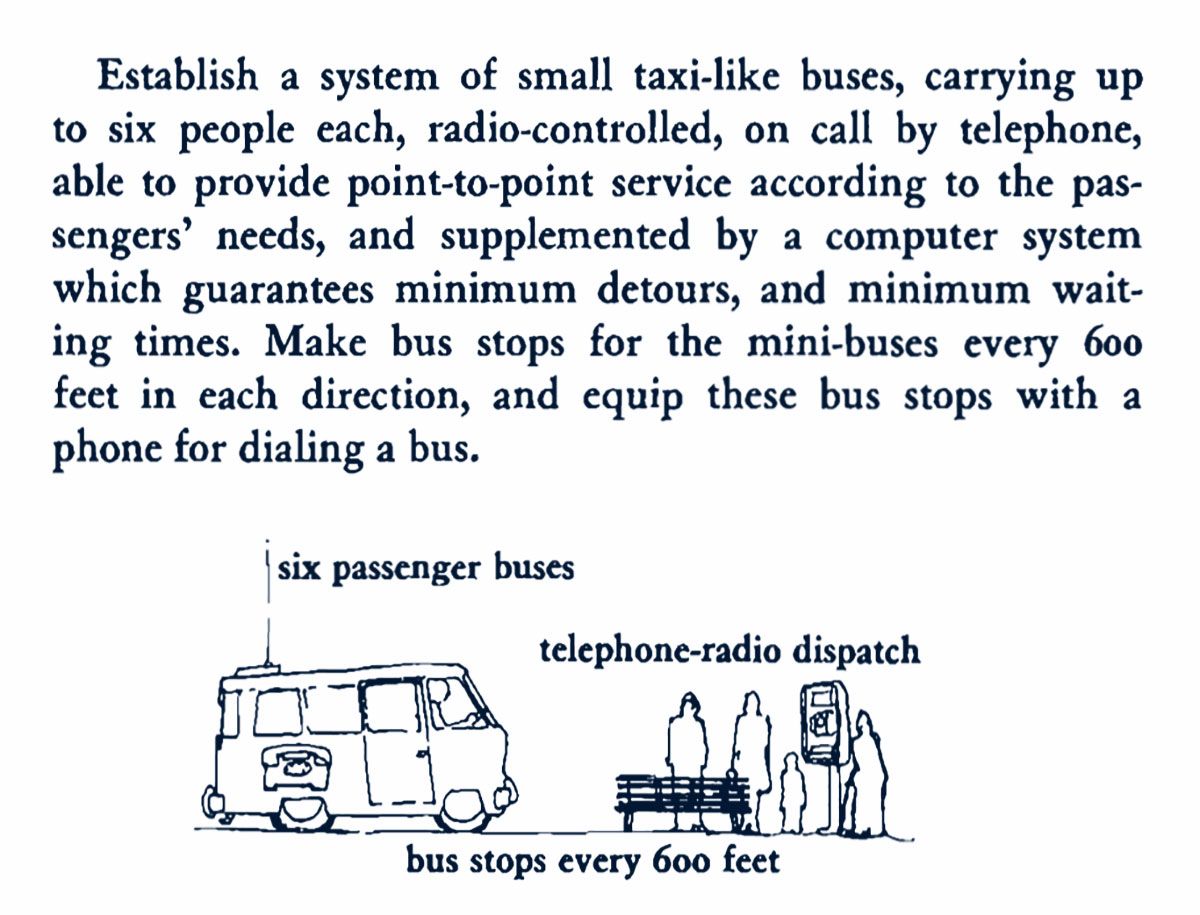

Christopher Alexander essentially described the Uber business model among his pattern languages, at No.20 with MINI-BUSES. We cannot know whether the founders of Uber were directly inspired or not by the precedent, but if they wanted it, it was there. And we know, thanks to Wright Steenson, how popular Alexander’s ideas were in some corners of the tech community.

Though less celebrated than Alexander’s patterns, Richard Saul Wurman’s Urban Observatory is another source of raw material. Wurman’s speciality is the mapping of information, toward the goal of making cities more legible and useful: "Wouldn’t a city – any city – be more useful and more fun if everybody knew what to do in it, and with it?".

Wurman published a series of city access guides, fold-outs on paper, that offered "a different kind of access to the city".

As Wright Steenson points out, "Wurman’s Urban Observatory was a ‘visual data center of the city and region’ with multimedia content showing the history and future of the city.”

This immediately brings to mind other possibilities opened up by digital technology.

Rather than printed maps, we now have GPS guided mapping. Rather than referential information across the urban space on a leaflet, we have the possibility of location based, responsive information delivery.

This was brought to life in a little known and now discontinued app called Detour – an audio augmented reality experience. In an image obsessed culture, augmented reality is typically associated with the layering of visual information via screens or glasses. However, Detour took a different approach, going back to AR’s origins.

If you have ever used an audio guide in an art gallery, you have experienced augmented reality. The audio guide delivers information relevant to what you are looking at. Detour does the same, but takes things to another level by integrating GPS, and location-based technology. The result is that the city can literally narrate its story to you, intimately in your ears, directly relevant to where you happen to be located.

Despite the riches buried within architectural practice, architects themselves mostly remain obsessed with form-making and form-giving.

This has to change, unless we want the rest of the world to pass us by.

Author: Molly Wright Steenson

Year of Publication: 2022

Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

amonle Journal

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.