The Timeless Way of Building

Uncovering the elusive 'quality without a name' that is at the heart of all living environments.

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, The other kind of A.I.

The quality without a name

Alive, whole, comfortable, free, exact, egoless, eternal. These are all words that Christopher Alexander uses to try to capture the quality without a name.

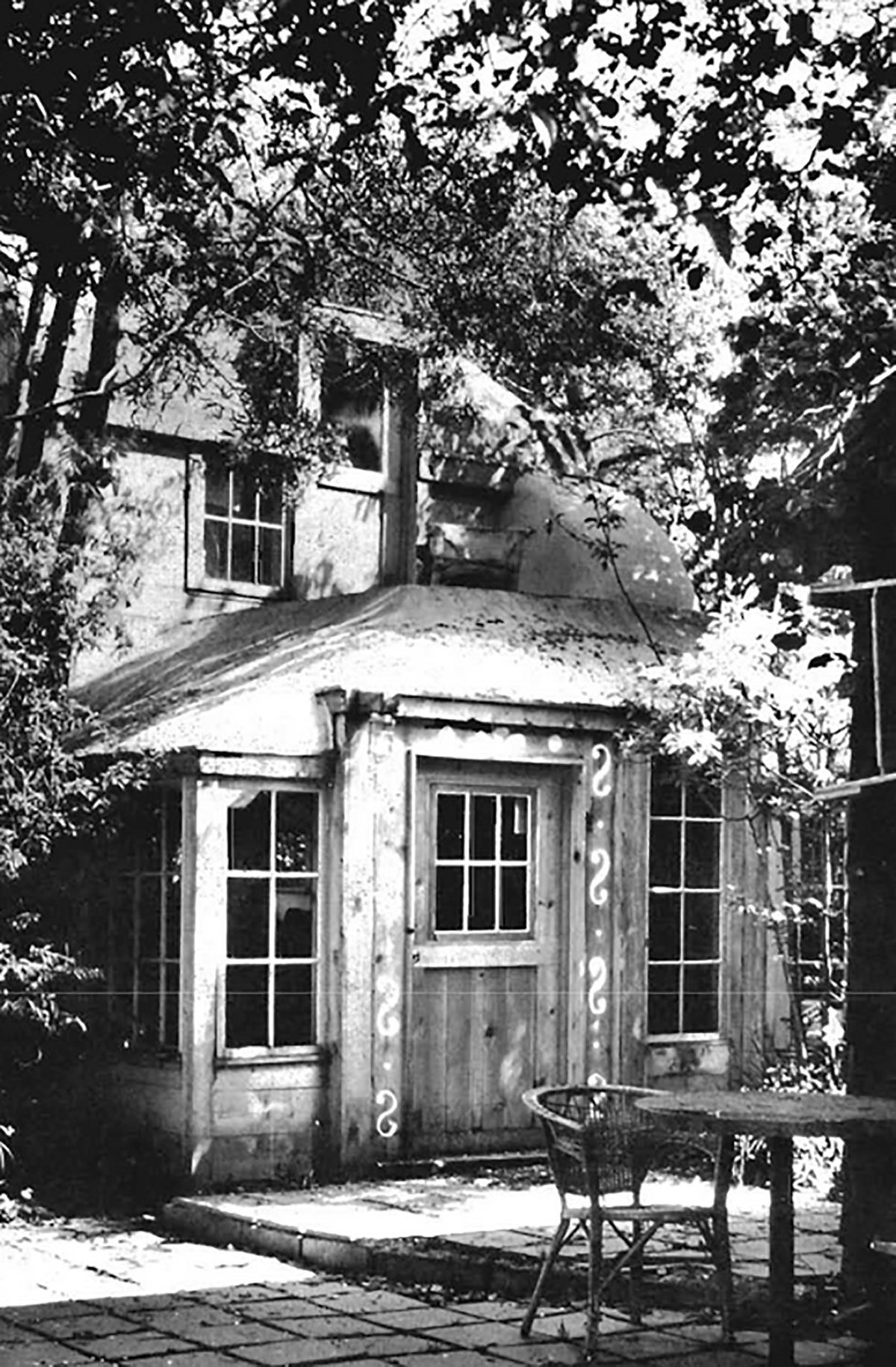

This is an elusive quality whose search drives the purpose of Alexander’s writing of the book. It is a quality which he asserts exists in traditional societies, in corners of gardens, on cosy sofas and other places that we likely take for granted. But once we recognise the existence of this quality, it comes into view in many aspects of our life.

Alexander suggests that it is an emergent quality, for us, coming out of the chaos of non-self-conscious human interaction with the natural order of things.

A joyful melancholy

This is not a book about architecture, at least not in the sense that you might find in the architecture section of a bookstore – either full of staged images or abstract theories on building and form. No, this is a book about faith.

It has more in common with religion, and perhaps philosophy, than with form-making and construction. The quality without a name, whose themes pervade the book, is deeply connected to our human nature, and to nature itself. Its recognition requires taking several steps back from the methodical and self-conscious world of professional practice.

Its search touches on matters of family life, health, and death, in ways that have very little to do with how to lay a brick on top of another with perfection, and much more to do with identifying and working with the patterns that a natural order already suggests.

The melancholy that Alexander touches on, in relation to the transitory nature of man and his creations, is reminiscent of the complex emotions that arise out of a musical infusion in the blues or in the craft of Japanese Wabi Sabi. It is a unique flavour of sadness that is accompanied by a sense of joy.

Delta Blues

The quality without a name, whose themes pervade the book, is deeply connected to our human nature, and to nature itself. Its recognition requires taking several steps back from the methodical and self-conscious world of professional practice.

The role of architecture

Through his advocacy for the recognition of the importance of living patterns for creating living buildings and towns, Alexander recasts the role of the whole of architecture.

He maintains that the purpose of architecture, insomuch as it is a creative act, should be the creation of a shared language of the built environment. He contrasts this open language of tradition with the compartmentalised, specialist and ultimately secret language of building, shared only amongst built environment professionals.

However, while he is careful not to use the word ‘tradition’ or ‘vernacular’, this, ultimately, is where his living environments can be found. He was writing at the time of an emerging post-modern approach to architecture, which looked back to history and to vernacular forms, for formal devices. This, however, was not at all what Alexander was after, since this intellectual reaction to modernism remained captured within a top-down design system, anathema to creating living environments.

Patterns

From identifying the quality without a name, Alexander moves on to his other core concept, patterns.

Patterns are the rituals (though he does not call them that), that represent the activities that are typical to a space – that happen over and over again there, and define the character of that space. Space simultaneously defines the character of those patterns.

Therefore, as with other branches of thought, such as phenomenology (with its intertwined relationship between body and space), and narrative environments (intertwined relationships between people, place, and experience), the irreducible element here is not an object, an element of geometry, or a single characteristic, but rather a relationship.

It is the relationship between experience and space which defines the pattern. They are interlocked, one anchored by the other.

Given that the irreducible element is a relationship, the core activity is dialogue.

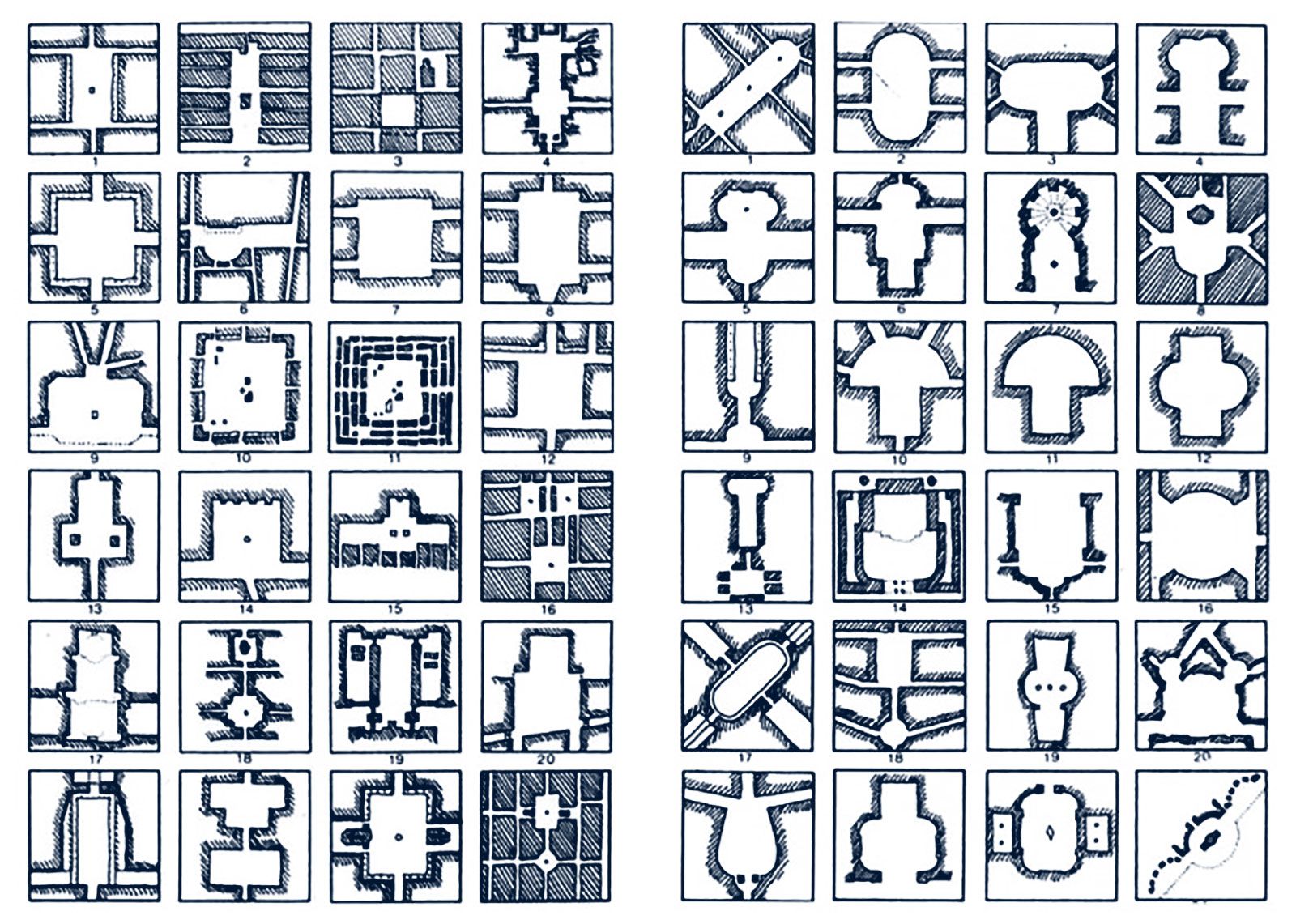

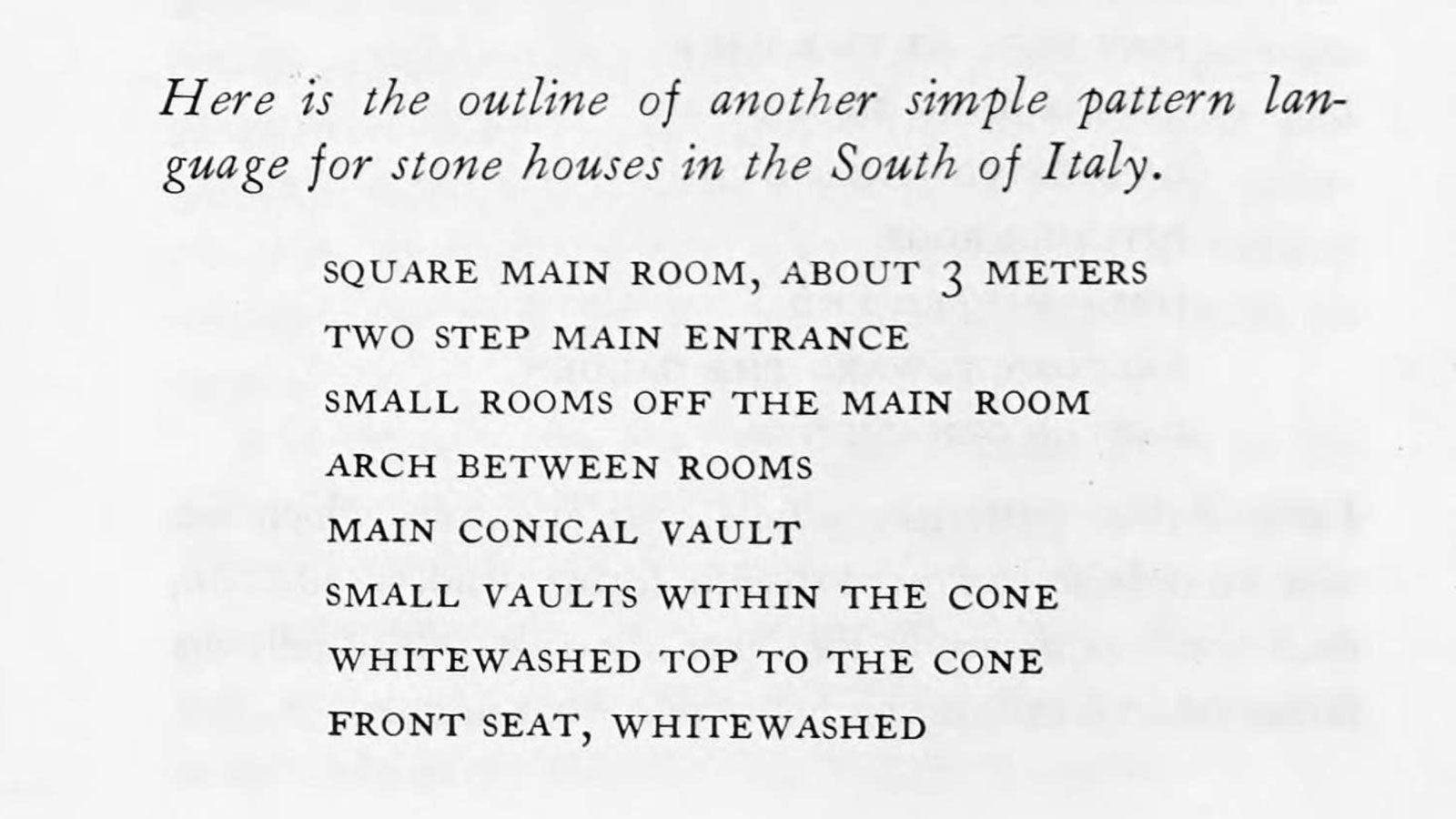

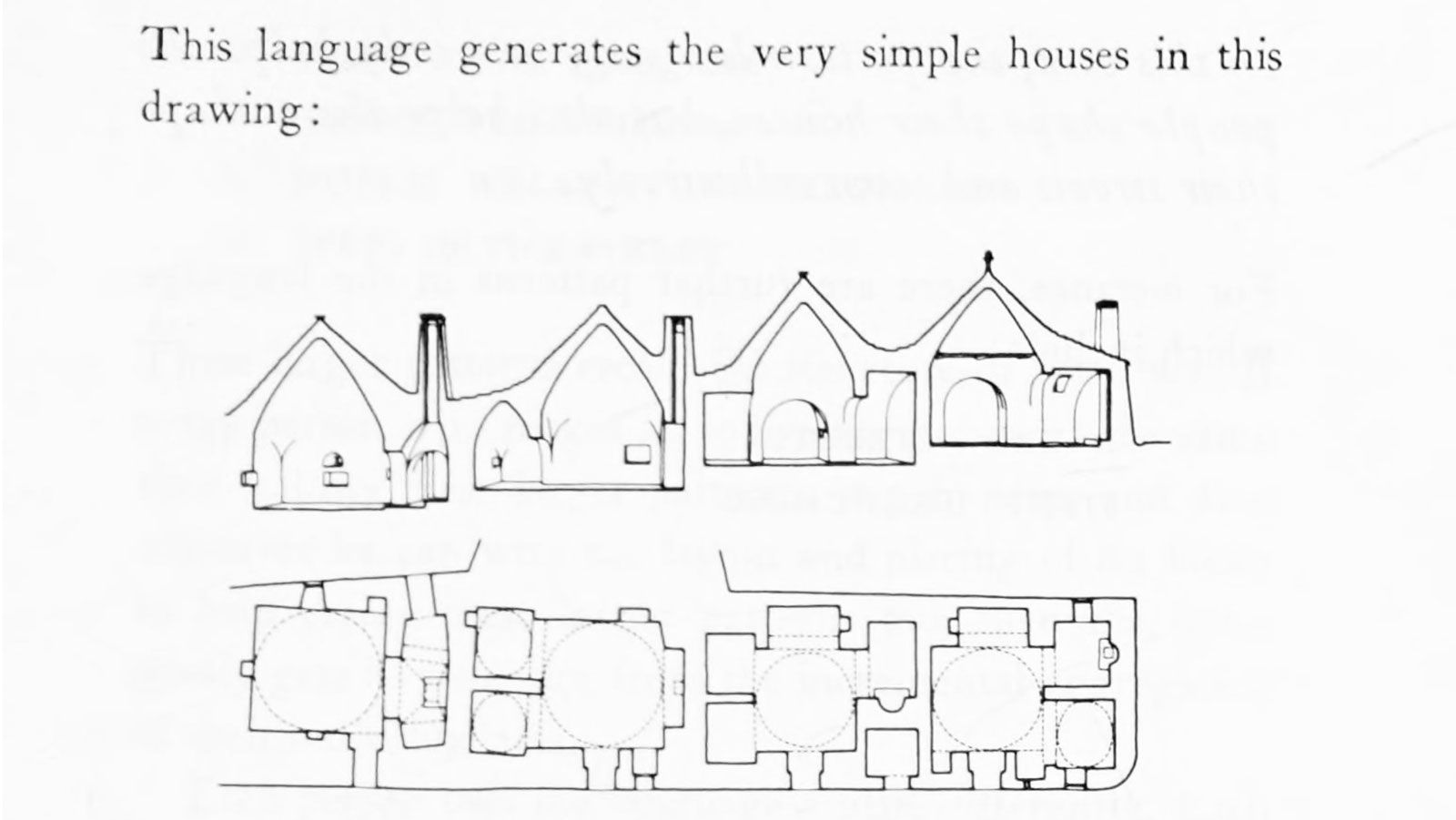

Patterns behave as a genetic or software code might, governing the choice-making that is involved in built forms. It is a procedural system which results in what we might consider a vernacular. It is not a cookie-cutter industrial system but rather a series of procedures which deliver small, local, and unique degrees of variety within a generally, overall, homogeneous whole.

The genetic code that Alexander refers to – these patterns, are similar to Hassan Fathy's definition of tradition - that “[it] is the social analogy of personal habit, and in art has the same effect, of releasing the artist from distracting and inessential decisions so that he can give his whole attention to the vital ones”. Both cases suggest the use of a rule of thumb, which does away with self-consciousness ‘design’, and makes way for the incorporation of wholesome, soulful and relatable elements.

Vernacular

About a third of the way into the book, Alexander arrives at a core differentiation between his timeless method and that which we are taught in architecture school – namely, how problems are solved.

The architect is taught that problem-solving in the built environment, though collaborative, is a hierarchical system with knowledgeable elites at the pinnacle and lowly operatives executing the work itself. It fits perfectly within a hierarchical class system and with the distribution of capital in so-called civilised societies. This compatibility is part of the reason it has endured for centuries.

Wherever hierarchal power is loosened, particularly in traditional societies and in rural environments, another problem-solving method takes hold. Alexander's view is that this method consists of using patterns. It is a convincing argument, and one within which the individual, regardless of his station, is empowered to change the built environment around himself.

Limitations

Alexander’s pattern language works best for single, standalone, new-build structures, on open plots of land. The barn pattern is a perfect example: “Make a barn in the shape of a rectangle 30-55 feet wide, 40-250 feet long …” etc. Try that in Central London!

He does venture into other examples such as a collectively built clinic, and an approach to repair, but it is inescapable that a pattern wants to be executed for as simple a project as possible. Introducing sequences of patterns for more complex structures generates a requirement for coordination and likely the presence of a confident, strong-minded, charismatic leader to see it through.

The reality of the 21st-century is that now, more than 50% of the world’s population lives in cities. Much of this is in high density state or informal housing – not many open plots of land to be seen.

The core contemporary challenge for pattern languages, if we wish to have living cities, is to find a way to make them relevant for these 21st century realities.

Faith

Jazz pianist Herbie Hancock shared an anecdote about an occasion when he was playing in one of the legendary groups led by Miles Davis. In the middle of his solo, he played a note which sounded completely out of place – a ‘wrong note’. He cringed. Davis immediately played a sequence of his own which turned this ‘wrong note’ into part of a coherent whole. Some might say that Davis ‘corrected’ the note, but what Davis showed Hancock was that there are no ‘wrong notes’, it all depends on what you play next.

Christopher Alexander asks us to take a similar leap of faith, to avoid taking a god’s eye view of the organisation of patterns, and deal with them, one after the other, in the faith that they will work themselves out. He asks us to let go of our fears and preconceptions when doing this. This is very similar to how we speak, given that we don’t enter into a conversation knowing every word that will be uttered. We essentially make it up as we go along, responding to the context and responses of others.

Alexander implores us to bring this approach to design.

—

We follow this up next week with a look at Alexander’s hugely influential, A Pattern Language.

Author: Christopher Alexander

Year of Publication: 1979

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

amonle Journal

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.