A Pattern Language

A Pattern Language is an instruction manual for humanity, to build everything from small objects to entire towns and cities.

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, The other kind of A.I.

Nuclear spring

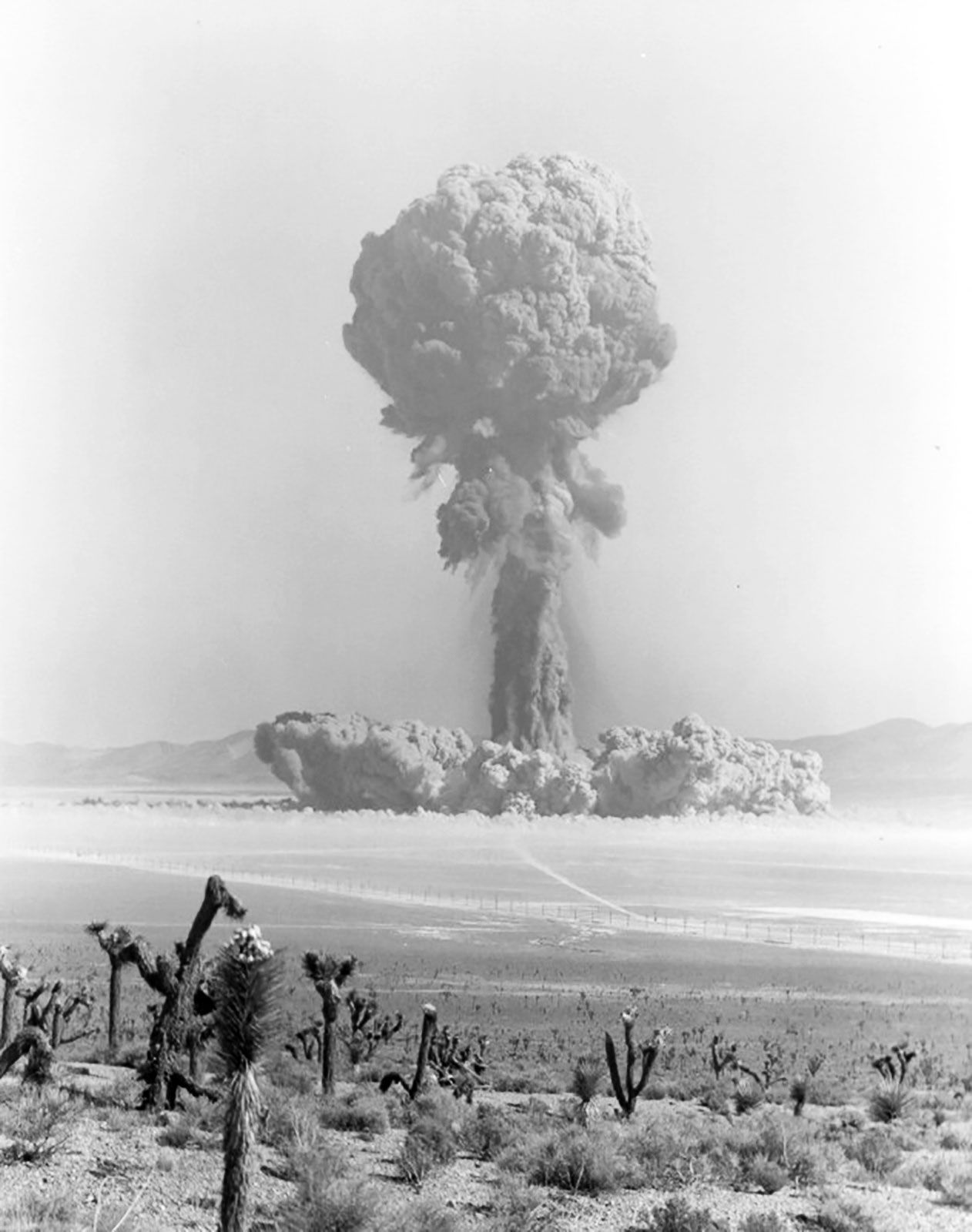

Perhaps you have noticed, if you have ever tried to purchase A Pattern Language, that it is only available in hardback. Perhaps, Alexander kept it this way so that at least a few copies would survive the very long term. Perhaps a few copies may even survive a nuclear holocaust.

A Pattern Language is an instruction manual for humanity, to build everything from small objects to entire towns and cities. If, god forbid, we ever did experience a nuclear holocaust, this book would be a key survival and reconstruction tool.

It is self-consciously written for the non-professional to follow a series of organisational rules (patterns), assembled and executed according to the relevance of the context (sequences), in such a way that they are as much an observation of the best of humanity, as a manual to recreate it.

As with volume one, The Timeless Way of Building, it works best in a cart blanche context, hence the ‘nuclear’ scenario. An opportunity for sure, but more of a challenge in these times of extreme population density in expanding, already built-up, urban centres.

This leaves us with the further challenge of how to apply the lessons contained, without waiting for a nuclear war.

A Pattern Language is an instruction manual for humanity, to build everything from small objects to entire towns and cities.

Transition

A Pattern Language was already an enormous brick of a book – over 1000 pages! But it is not a whole book. It is the second part of three volumes, and it is essential to read volume one before venturing into this one. Despite its length, Alexander does not take the time at the beginning to say “here is my explanation of the concepts that I am about to present to you …” etc.

No, he goes straight into explaining, “this is process No.1; this is process no.2 … Etc“. If you haven’t read The Timeless Way of Building (volume one), then you have been deprived of a transition, and starting the book is jarring.

It is a little surprising that A Pattern Language is so much more well-known than its predecessor. Granted, it is ‘the solutions book’, but A Timeless Way of Building is certainly ‘the concept book’.

That is all well and good …

Around the midpoint of the book, Alexander walks us through a scenario using his sequences and patterns to design a structure. As in traditional societies, and historically in more developed societies, much of the work and thinking is carried out in situ – on site, with materials that will ultimately be used to build a structure, and by the people who will inhabit it.

Alexander talks about marking out layouts with string and bricks on the ground, and measuring by pacing. He implores us not to use paper. That is all well and good, but the reality is that in almost every society, now, globally, the act of building takes place within a highly regulatory environment.

The means of communication within that regulatory environment typically include a combination of documents (drawn and written) and inspections, the very things that Alexander wants us to avoid. It is no accident that the building industry has not escaped the standardisation of all other industries, and that the standardised products that emerge out of it help to lubricate our way through the regulatory process.

Therefore, unfortunately, it is typically easier to hire a professional, have them use standardised products, and work in standardised ways – i.e. on paper, with drawings etc. The sequence/pattern/intuition method has a romantic ring to it, and accordingly, a slightly unrealistic one. It might be suitable for temporary or some rural structures, but does not answer to the demands of permanent and highly regularised ones.

RIBA Plan of Work: Both the reflection of and a precipitator of the highly regularised architectural professional landscape

Universal values

We have to get all the way to page 742 (of 1,171), with the pattern OPEN STAIRS, for Alexander to reveal his underlying values – namely, a belief in a free, anarchist society, with “a voluntary exchange of ideas between equals”.

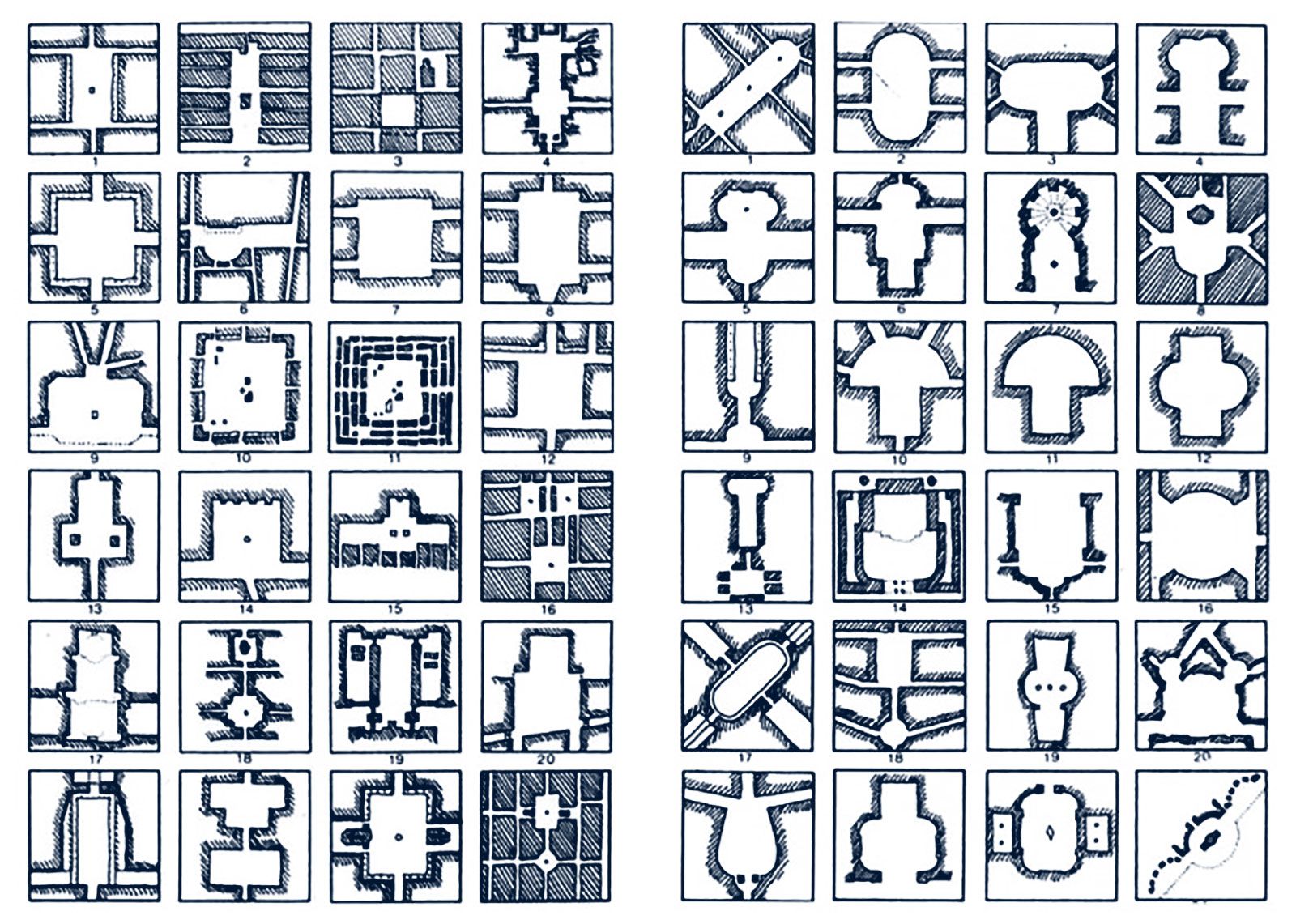

The entire premise of A Pattern Language is that we all, intrinsically, know how to build, and should be empowered to do so without centralised authority, or the need for protectionist professional input. The Timeless Way of Building posed the question “what works?”. A Pattern Language (humbly) answers, ”this works”, 253 times.

Alexander has scoured of the world for examples of spatial decision-making that enriches the human soul. In fact, he does repeatedly refer to Berkeley and Peru, we assume places that he has lived for some time, but his central message here, together with the message in the previous volume, is that the values and methods that he is attempting to excavate are universal.

The Timeless Way of Building posed the question “what works?”. A Pattern Language (humbly) answers, ”this works”.

Gradual stiffening

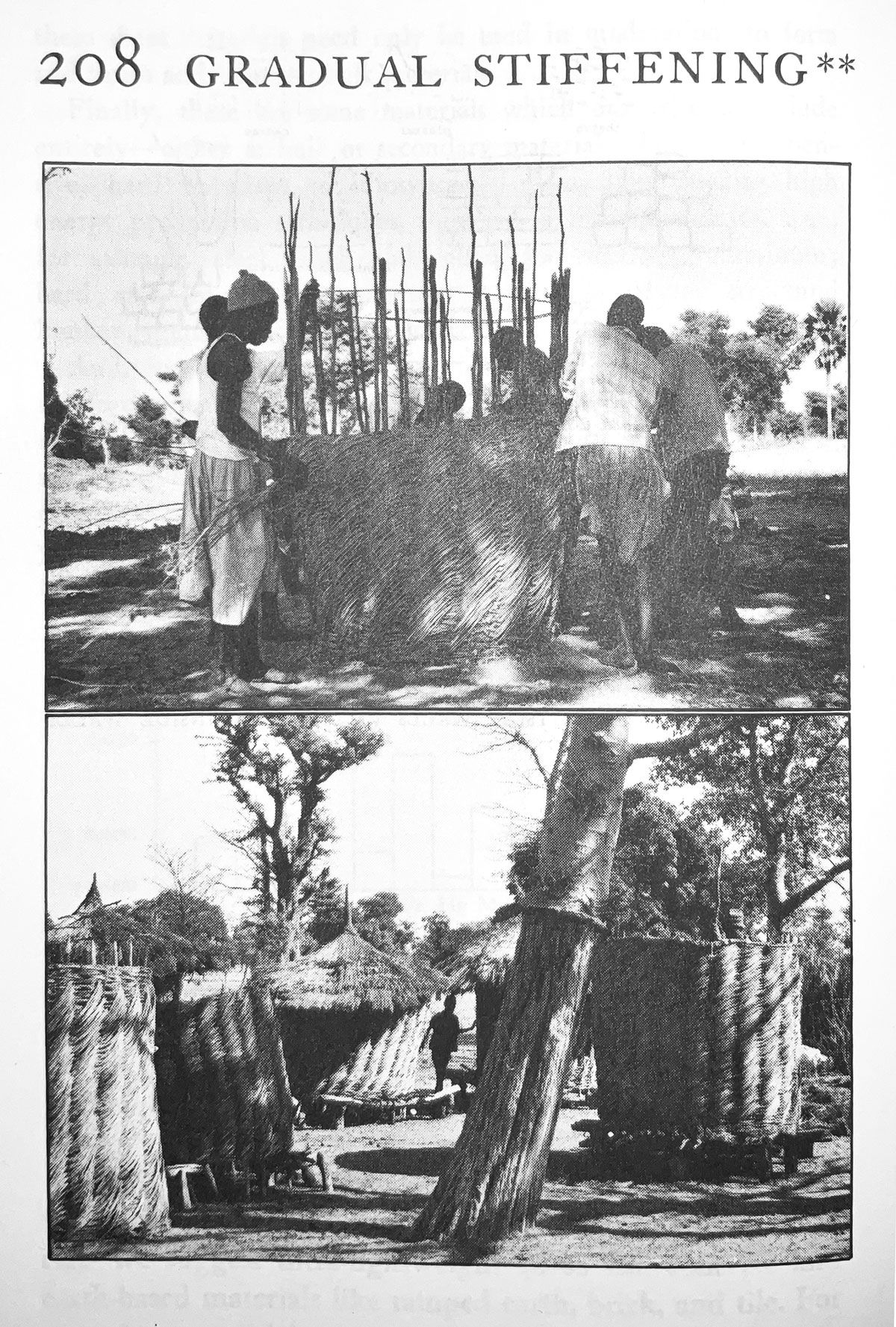

If we were to choose a single pattern that embodies the authors' beliefs, the message of this book, and indeed that of the preceding book (A Timeless Way of Building), it would be GRADUAL STIFFENING.

We encounter this pattern towards the end of the book, in a section dealing with construction matters, but the approach outlined captures the essence of what Alexander is trying to effect in the building industry as a whole. His pattern (or principle) of gradual stiffening can be summarised by imagining that if we want to build a unit of space, whether a room or a building, we start with the overall form ‘flimsily’ and gradually make it whole.

The driving values of this principle are that we do not need to prescribe all the details of a unit of space before it is built, but rather, we can sketch it out in place by starting with its footprint and, with confidence, filling the gaps as we go, to enclose it, and make it spatially and structurally sound – stiffening it.

It is a belief system in which we are implored to get going without necessarily knowing all the details of the final destination, but with the confidence that each step can make the previous step relevant. It is an act of faith. This is facilitated by two key components: materials that are conducive to manual use, and an improvisational mindset comparable to the use of language.

An approach such as this goes against the most fundamental architectural orthodoxy, which demands that buildings are set out and defined in detail, in advance. Incidentally, though, the vast majority of buildings, for the vast majority of human history, have been constructed in the way that Alexander defines. It is, indeed, the timeless way of building.

Culture shift

There are so many ideas which may intuitively strike the reader as wholesome and positive in many ways. Alexander presents examples, typically from traditional societies, which have not been transformed by industrialisation. Ideas such as his observations about a ritual of bathing (pattern 144, BATHING ROOM), rather than just ‘cleaning’; or sleeping in an alcove rather than making a full bedroom (pattern 188, BED ALCOVE); or even COMMUNAL SLEEPING (pattern 186), resonate in a way that might leave us feeling as though something in society has been ‘lost’.

Perhaps, if we implemented his suggested patterns rigorously, we would live more wholesome lives. However, the degree of culture shift that would be required is enormous, and would necessitate an ‘exit’ from our ‘developed’ societies, to some sort of off-grid, self-sufficient existence.

Regardless of the perceived benefits of timeless, living values, the challenge remains, how do we transform our industrial, urban environments using the lessons that Alexander and co have left us with.

Authors: Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa & Murray Silverstein; with Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King & Shlomo Angel

Year of Publication: 1977

Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Enjoyed the read? Now watch the films.

amonle Journal

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.